1. Introduction

The institutional mechanisms of an economy can facilitate transactions, safeguard property rights and stimulate or discourage behaviors and entrepreneurship actions. Many factors determine these achievements: rules and regulations, the quality of government, the availability of education, and the ambient culture. Many of these factors fall under the heading of institutions and constitute the constraints on behavior imposed by the state or societal norms that shape economic interactions.

Those countries with institutional weaknesses have inefficient labor, developed product and capital markets (Ciravegna, Lopez & Kundu, 2013), which in turn will limit investments in relevant activities such as innovation in production processes (Zhang, Tan, Ji, Chung & Tseng, 2017). Given that institutions are in charge of creating and enforcing the rules of the economy, they play a moderating role through three pillars − regulatory, normative and cognitive − each focused on different institutional dimensions.

Innovation and internationalization are among the activities usually affected by the country's institutional weaknesses. Developing these activities has positive effects on countries such as increased employment, steady economic growth, higher productivity of the company, and company survival in local and external markets (Kijek & Kijek, 2019;Van Lacker, Mondelaers, Wauters & Van Huylenbroeck, 2016). Therefore, it is necessary to provide companies with institutional mechanisms that allow them to overcome institutional weaknesses and conduct their activities to achive better performance.

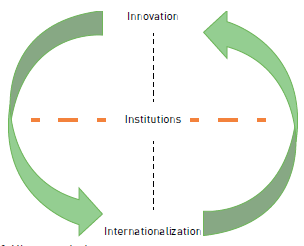

Therefore, the main objective of the article is to give recommendations that will enable countries to improve their institutional frameworks and thus they can benefit from the positive effects of innovation and internationalization strategies. The development of these activities makes it possible to build whatBrodzicki (2017) has called a virtuous circle, in which higher levels of innovation increase the probability of internationalization of companies and consequently they will have to continue innovating to prevail in external markets. As shown in Figure 1, institutions are twoway moderating agents (see dotted line in the graph), since through their pillars they influence the levels of innovation and internationalization, facilitating the existence of the virtuous circle.

To achieve the main objective, this paper conducts a review of relevant investigations that have been published in different scientific journals, with the aim of synthesizing some basic ideas that allow the development of an integrative institutional framework for future research on innovation and inter-nationalization strategies. Four key words are used when searching for articles in databases: institutions, innovation, internationalization, and entrepreneurship. The selected articles are conceptually reinforced with precursor classic research in the selected topic, for example, articles byNorth (2001) andCoase (2009) have been included to analyze conceptual theories on institutions. Developing this theoretical framework allows the introduction of relevant concepts and, at the same time, contributes to a better understanding of how institutions influence the spillover of innovation and internationalization strategies on the economy of the countries. This knowledge will enable us to give recommendations to managers and policy makers for applying in growth strategies and economic development policies of countries.

Below, the article presents the methodology applied in the search of studies that will build the theoretical framework. Subsequently, the paper focuses the theoretical analysis on institutions and presents key concepts and their linkages with entrepreneurship, innovation and internationalization decisions. The fourth part of the paper presents some recommendations for possible strategy and policy improvements that can be implemented based on the three pillars, with the purpose of achieving an adequate institutional framework in any country and thus overcoming institutional weaknesses. Finally, the paper summarizes the main conclusions of the study, and it addresses some future research areas.

2. Methodology

The main methodological approach of this research is the analysis of the existing bibliography from databases containing publications of scientific journals on the topic. We analyze the articles contained in two scientific databases: ScienceDirect (Elsevier) and ResearchGate. These databases were chosen because their search processes in indexed databases allow to consult relevant academic studies published in different journals with different topics, aims, and audience. Both databases provide users with a vast number of publications which, combined with the ease of access to documents, facilitates an indepth analysis.

The first step carried out was the definition of a search strategy.Brodzicki (2017) article becomes a main source through the concept of the virtuous circle between innovation and internationalization, and the importance of institutional frameworks for companies and countries to take advantage of benefits of mutual influence. Once the area of research and the databases to be consulted have been defined, the "text analysis" method is applied according toZupic and Čater (2015) following the association of words based on titles, abstracts or keyword lists. For data collection, four key words were defined: "Institutions", "Innovation", "Internationalization" and "Entrepreneurship". The search was conducted in English in order to have a greater number of articles to choose from, we covered the period 2004-2020 and applied a filter to select only publications classified as articles.

Subsequently, the search equation was defined to obtain the records for the period under analysis. The search in ScienceDirect was "Institutions AND Innovation AND Internationalization AND Entrepreneurs hip", resulting in a total of 852 articles. The search in ResearchGate limits the results to 100 articles per query. To avoid this limitation, six searches linking two by two the keywords were run as follows: "Insti tutions AND Innovation", "Institutions AND Internatio nalization", "Institutions AND Entrepreneurship", "In novation AND Internationalization", "Innovation AND Entrepreneurship" and "Internationalization AND Entrepreneurship", obtaining a total of 600 articles. The search strategy and the results are summarized in Table 1 below, adding the number of documents se lected according to the database.

Table 1Results of the article search and selection by database.

| Bibliographical tool | Search equations | Found documents | Used documents |

|---|---|---|---|

| Science Direct | (“Institutions AND Innovations AND Internationalization AND Entrepreneuship”). | 852 | 30 |

| Research Gate | (“Institutions AND Innovation”), (“Institutions AND Internationalization”), (“Institutions AND Entrepreneurship”), (“Innovation AND Internationalization”), (“Innovation AND Entrepreneurship”), (“Internationalization AND Entrepreneurship”). | 600 | 35 |

Source: own elaboration.

For the selection of the articles, the title and abstract were analyzed in order to select those that theoretically contribute to the conceptualization of the virtuous circle between innovation and internationalization and the importance of an institutional framework that promotes entrepreneurship and facilitates the existence of the circle. The selected articles (65 in total, 30 contained in ScienceDirect and 35 in ResearchGate) are coceptually reinforced with some classic research precursors in their fields, such as the oned carried out byNorth (2001) andCoase (2009) to address theories on institutions, or the contribution ofJohanson and Valhne (1977) in the theory of internationalization.

Table 2 presents the selected articles according to the scientific journal they belong to, and Table 3 presents the articles by the name of their authors and the year of publication, according to the keyword with which they theoretically contribute to the research. For instance, authors such asNewburry, McIntery and Xavier (2016) appear in more than one keyword as their work discusses topics associated with three of the keywords used in the methodology.

Table 2Number of selected articles and their percentage participation per scientific journal.

| Scientific journal | Total | Percentage of participation | Scientific journal | Total | Percentage of participation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Journal of Business Research | 5 | 7.69% | Women´s Studies International Forum | 1 | 1.54% |

| Research Policy | 3 | 4.62% | Higher Education Policy | 1 | 1.54% |

| International Journal of Emerging Markets | 3 | 4.62% | Journal of Innovation & Knowledge | 1 | 1.54% |

| International Entrepreneurship and Management Journal | 3 | 4.62% | Economics: the Open-Access, Open-Assessment e-Journal | 1 | 1.54% |

| Small Business Economics | 3 | 4.62% | Long Range Planning | 1 | 1.54% |

| Technological Forecasting & Social Change | 3 | 4.62% | CIRIEC-España Revista de Economía Pública, Social y Cooperativa | 1 | 1.54% |

| International Business Review | 3 | 4.62% | International Business Research | 1 | 1.54% |

| Sage Journal | 2 | 3.08% | Dados | 1 | 1.54% |

| Structural Change and Economic Dynamics | 2 | 3.08% | Industrial and Corporate Change | 1 | 1.54% |

| Journal of International Business Studies | 2 | 3.08% | Journal of Economic Dynamics and Control | 1 | 1.54% |

| Journal of International Management | 2 | 3.08% | Foresight and STI Governance | 1 | 1.54% |

| Industrial Marketing Management | 2 | 3.08% | Journal of Global Entrepreneurship Research | 1 | 1.54% |

| SSRN Electronic Journal | 2 | 3.08% | Technovation | 1 | 1.54% |

| Entrepreneurial Business and Economics Review | 1 | 1.54% | Journal of Development Economics | 1 | 1.54% |

| International Journal of Industrial Organization | 1 | 1.54% | International Atlantic Economic Society | 1 | 1.54% |

| Journal of International Entrepreneurship | 1 | 1.54% | Journal on Innovation and Sustainability RISUS | 1 | 1.54% |

| Procedia - Social and Behavioral Sciences | 1 | 1.54% | Asia Pacific Journal of Management | 1 | 1.54% |

| Business Process Management Journal | 1 | 1.54% | The Journal of Technology Transfer | 1 | 1.54% |

| Business Horizons | 1 | 1.54% | Tehnički Vjesnik | 1 | 1.54% |

| Journal of Cleanear Production | 1 | 1.54% | Academy of Management Annual Meeting Proceedings | 1 | 1.54% |

| Journal of Entrepreneurship and Public Policy | 1 | 1.54% | Management international / International Management / Gestiòn Internacional | 1 | 1.54% |

| Economics of Transition and Institutional Change | 1 | 1.54% |

Source: own elaboration.

Table 3Articles associated with each keyword by authors.

Source: own elaboration.

This literature review process seeks to introduce relevant concepts related to the proposed research topic, which will be presented in detail in section three of this paper, and at the same time, it provides a source of information to list several recommendations to improve the institutional framework of a country, that will be addressed in the fourth section of this document.

3. Institutions: Link with entrepreneurship, innovation and internationalization

In the first chapter of the book "Essays on Economics and Economists",Coase (2009) considers that "...a market economy of any importance is not feasible without adequate institutions." (p.16), such institutional structure is composed of standards and regulations that, for the author, allow to quickly resolve transactions.

Some other authors such asHayek (1966) also emphasizes that the main function of institutions and regulations is to impose limits on the actions that can be performed.Masten (1996) stresses that regulations should not tell people what to do, but what not to do.Dikson and Weaver (2008) also state that an entrepreneurial orientation is promoted by an adequate institutional framework and acknowledge that legal systems must safeguard property rights and their enforcement matter be-cause they affect the transactional trust between parties. The influence of institutions is not only found in entrepreneurial orientation;Bucelli, Costa Neto and Vendrametto (2014) find a positive correlation between the institutional level and the type of external environment, where a higher level of the former translates into a higher degree of stability in the economy in general.

The authors mentioned above allow us to outline some theoretical ideas about institutions, the central axis of this paper. The development of entrepreneurship, innovation, internationalization, and other elements of a country's economic life are related to the institutional framework. To consider the interrelationships under study, it is necessary, first, to deepen the analysis of institutions as the main variable of the external environment of any economy. The favorable effect of an adequate institutional framework in the economy has been the focus of several studies. According toNorth (2001), this framework will not be efficient, as this requires complete information on the part of all agents, which differs from the asymmetry of information characteristic of the economy. Despite the above, it is possible to try to build an adequate institutional framework to solve problems such as underdeveloped capital, labor, and product markets that generate institutional weakness and condition companies (Ciravegna, Lopez & Kundu, 2013). Over-coming institutional weakness should be a goal of any country; for example,Zhang et al. (2017) find that legal inefficiency leads to dysfunctional competition, affecting the ability of businesses to benefit from new products or processes developed.Young, Tsai, Wang, Liu and Ahlmstrom (2014) also mention that institutional weakness globally restricts companies from emerging markets, a fact reinforced byWu and Chen (2014) who conclude that a better home country institutional environment promotes the expansion of companies in advanced foreign markets.

However, it should be noted that an adequate institutional framework should not have many regulations and laws, since this can hinder growth (Davidsson, 1991), and there is no positive relationship between frameworks with robust laws and regulations and solutions to business problems (Zevallos, 2003). Although Latin American countries have tried to overcome the political and economic instabilities characteristic of the late 20th and early 21st centuries, as highlighted byZevallos (2003), difficulties persist in their institutional frameworks, translating into external and internal distrust and having a negative impact on aspects such as investments. The author indicates that despite the existence of many laws, solutions to the problems of companies, especially smaller ones, are not being solved in the region.

Trevino, Thomas and Cullen (2008) emphasize that a country's institutional framework is built based on the three pillars: regulatory, cognitive and normative. The authors indicate that the regulatory pillar relates to existing government policies, laws and regulations that promote or restrict behaviors; on the other hand, the normative pillar focuses on the social norms, beliefs and values that individuals share, this pillar may or may not encourage vital aspects of economic life such as innovation. Based on the mentioned above, Çingitas and Ecevit (2019) highlight that in the case of Turkey, the low value that exists in the business network for innovation is related to its low degree of development.Spencer and Gomez (2004) determine that this pillar also influences the importance given to entrepreneurs, which can boost such activity. Lastly, the cognitive pillar refers to widely shared knowledge.Gacel (2012) acknolewdeges that this pillar can stimulate internationalization by applying an international educational approach, improving the levels of knowledge available to companies wishing to internationalize.

Busenitz, Gomez and Spencer (2000) also mention that it is necessary to understand the dimensions of a country's institutional profile, which is built based on the three pillars mentioned above. The institutional profile makes it possible to observe the strength or weakness of a country in each pillar, since it reveals the efficiency or weaknesses of the policies implemented to stimulate entrepreneurship among other activities (Manolova, Eunni & Gyoshev, 2008). Current tools that facilitate this task include programs such as theGlobal Entrepreneurship Monitor (GEM) according toReynolds, Bosma, Autito, Hunt, De Bono, Servais, Lopez-Garcia and Chin (2005).

As a conclusion, institutions exercise power in the economy through their three pillars, stimulating or discouraging behaviors and actions. Therefore, these pillars have a mediating role and influence the economic development of a country in various ways. We first analyzed its connection with entrepreneurship, taking this as a reference of business activity in the economy.

3.1 Institutions and entrepreneurship: The importance of the external environment in the development of the company

For innovation and internationalization to be possible in an economy, it is necessary to have agents that can implement these activities: the companies.Schumpeter (1944) emphasizes that human beings find in economic activity the mechanism to satisfy their needs, being the companies the scenario in which the productive process takes place.West, Bamford and Marsden (2008) − based on a study applied to Latin American economies − consider that business development is the gateway to economic vitality, in which entrepreneurship is the concept most associated with the creation and stability of the company.

Özsungur (2019) finds emotional factors (fulfilling dreams), pull factors (developing innovations), push factors (proving oneself), among the reasons for entrepreneurship. Additionally,Kahneman (2011) considers that risk aversion is a characteristic variable that differentiates the entrepreneur from the employee, which is why it becomes another necessary element for entrepreneurship. The above motivations and some others have been classified in the literature into two main reasons for entrepreneurship: opportunity and necessity. The first is related to motives such as independence, contributing to society, or implementing an idea. Entrepreneurship based on necessity is linked to the desire to have an income in the presence of scarce forms of employment.

Either of the two reasons analyzed for entrepreneurship requires a close and favorable connection with its external environment.Arenius and Minniti (2005) stipulate that the individual's environment influence entrepreneurial activity. As an example, the work ofManolova, Eunni and Gyoshev (2008) conclude that while in Hungary and Latvia the availability of knowledge (cognitive pillar) limits entrepreneurship, in Bulgaria entrepreneurship is limited by laws and government policies (regulatory pillar). Based on the mentioned above,Ali, Kelley and Levie (2019) find that improvements in the institutional and market context are conducive to entrepreneurship.

West, Bamford and Marsden (2008) find that in emerging countries such as Latin American ones, the use of entrepreneurship as an instrument for growth is complex. Therefore, the factors thatAmorós, Poblete and Mandakovic (2019) found in the region to promote entrepreneurship become relevant: applying policies to support entrepreneurship (regulatory pillar), a higher level of education (cognitive pillar), and international orientation accompanied by innovations − for which it is necessary that innovation is socially valued (normative pillar).

When studying the relationship between institutions and entrepreneurship, several moderating variables appear, for example,Dempster (2017) addresses corruption as an important issue. The author determines that there is a compensation between productive activities that generate value and those illegal unproductive ones where private individuals benefit from public resources. On the other hand,Wu (2019) demonstrates that in the presence of corrupt acts, such as the payment of bribes to public officials, companies that commit these acts will suffer from lower innovation capacity and productivity. Therefore, corruption should be perceived as a variable that influences institutional weakness.

Another salient aspect of the link between institutions and entrepreneurship is found in the studies carried out byBosma, Content, Sanders and Stam (2018); andAcs, Estrin, Mickiewicz and Szerb (2017), who conclude that productive entrepreneurship promoted by institutional quality contributes to economic growth. The importance of institutions promoting entrepreneurship is based on the idea that companies are the organizations where innovation and internationalization take place, aspects that, as mentioned above, improve a country's economic vitality. Next, the relationship between institutions and innovation is introduced.

3.2 Institutions and innovation: A first look at Brodzicki's virtuous circle

Previously, we considered the link between the institutional framework and entrepreneurship, taking the latter as a measure of the entrepreneurial network of an economy. The study now focuses on the relationship between institutions and innovation.Kijek and Kijek (2019) comment that the role of innovation in companies is diverse, contributing to job creation, economic growth, and boosting productivity. Additionally,Van Lacker et al. (2016) state that innovation is crucial for the survival of organizations. These ideas highlight the importance of considering how institutions can influence growth and survival decisions. Through a case study analyzing innovation in Canada and the United States,Ranasinghe (2017) finds that tax or subsidy policies and regulatory burdens affect the difference in costs of engaging in innovative activities between the countries, resulting in Canadian innovation spending being lower than that of the United States.

However, there are some other variables that influence the degree of innovation, such as the country's income level measured by Gross Domestic Product per capita mentioned byAmorós, Fernández and Tapia (2012); the size of the company that facilitates innovative persistence (Córcoles, Trigero and Cuerva, 2016); or the planning and management of innovation within the company (Peraza, Gómez and Aleixandre, 2016).

According to the literature review, the institutional framework through its three pillars appears as one of the main variables affecting innovation.

Analyzing macro and micro institutional environments,Gao, Shu, Jiang, Gao and Page (2017) found that political and commercial ties have a positive effect on innovation. R+D is considered one of the most important variables in increasing innovation in a country. By doubling R+D intensity the probability of reporting a process innovation is 12% higher and a product innovation is 29% higher, according toBaumann and Kriticos (2016).Peraza, Gómez and Aleixandre (2016);Córcoles, Triguero and Cuerva (2016); andPellegrino, Piva and Vivarelli (2011) come to the same conclusion, thus evidencing some consensus in the literature on this topic. A way to appreciate the effect of R+D on innovation is the generation of patents.Geldes, Felzensztein and Palacios-Fenech (2017) conclude that by promoting the development of patents the probability of propensity to innovate in the Chilean manufacturing industry is 215.8%, in the case of the services industry the increase is 115.8%.

Among the actions that can be undertaken to achieve these results are an increase in the financing capacity of governments (regulatory pillar), the training of human resources (cognitive pillar) and the valuation of innovation disseminated among entrepreneurs (normative pillar). According toLederman, Messina, Pienknagura and Rigolini (2014), the low levels of innovation in the Latin American region are reflected in the scarce development of patents and the lower proportion of R+D expenditure, which limits the development of business innovation cultures. The authors also indicate that in Latin America, unlike other regions, investment in innovation comes mainly from the public sector, with less participation by companies, which prevents such a culture of business innovation from being possible, showing the need for a framework that stimulates business investment in innovation.

To achieve better levels of innovation, it is also necessary for the institutional framework to be the right setting for competitiveness among the agents acting within it.Amorós, Fernández and Tapia (2012) find that competition in different sectors has led to the creation of a greater number of companies, improving their innovative performance. At this point, the regulatory pillar must facilitate the creation of new companies, and in turn, provide the appropriate markets for competition to exist.Li (2017) considers that if the company's strategy is based on competitiveness when offering services or manufacturing products, the possibility of entering and remaining in international markets increases. The importance of innovation in the competitiveness strategy is addressed in the research ofNewburry, McIntyre and Xavier (2016), who found that success of Brazilian and Chinese multinationals in more sophisticated international markets has to do with an increase in innovation in their internal processes.

The link between institutions and innovation also impacts economic growth.Silve and Plekhanov (2018) show that countries with stronger economic institutions specialize in more innovation-intensive industries, thus innovation becomes a channel through which higher quality institutions achieve better long-term growth. This impact of innovation on economic growth is also observed in the study made byQamruzzaman (2017).

In synthesis, having an institutional framework that favors competitiveness and in turn stimulates innovation is essential to guarantee the entry of companies into international markets, which will favor the growth of firms and the economic growth of the host country. Moreover, innovation is promoted more in some countries than in others, mainly due to the institutional structure. Governments can act in aspects such as the promotion of R+D and patents, access to resources, and the improvement of human capital, among other variables to improve their results. A case study evidencing the need to maintain institutions capable of promoting innovation and future economic growth is presented byVermeille and Kohmann (2016). They consider that France has reached a breaking point where current institutions do not meet the needs of its current economy, so it must equip itself with institutions that will enable to achieve these goals of innovation and growth. By improving levels of innovation, institutions can facilitate companies' access to external markets, but to remain in those markets, companies will need to continue innovating thus creating a virtuous circle, which is the focus of the following section.

3.3 Institutions, innovation and internationalization: The three i's in the virtuous circle

Institutions act as a two-way moderator influencing the degree of innovation and the degree of internationalization of a company. Previously, we mentioned the relationship between institutions and innovation to deepen the elements of the virtuous circle proposed byBrodzicki (2017). Now, we analyze the internationalization strategy.

Peng, Wang and Jiang (2008) state that an institutional base with an international focus is a primary element of the strategic tripod in emerging economies, as institutions are the rules of the game within an economy and their structures provide the necessary conditions for a company to compete in the global market (Borzaga & Depedri, 2012). Therefore, institutions determine the context of the inter-nationalization strategies that companies may adopt.

Among the internationalization theories, the Uppsala model is widely accepted as a reference. This model is based on the progressive increase of commitments to foreign markets, which will be ac-quired as the company gains knowledge of foreign markets and operations. This was an essential aspect of the study developed byJohanson and Vahlne (1977), authors who determined that the initial exchange will be developed with markets with greater psychic proximity (similar language and culture, proximity in political and educational systems), to later develop exchanges with countries with a greater distance. The same authors, updating their research, state inJohanson and Vahlne (2009) that more than psychic distance, the key explanation factor in internationalization processes relies on uncertainty, being fundamental the build trust and create knowledge in the development of relationships. To provide such trust, an adequate institutional framework is required, and countries must overcome some problems such as corruption.

Regardless of the type of strategy to be implemented,Xiao et al. (2013) consider that governments, especially those at a higher level such as a country's central government, should implement institutional changes that encourage local businesses to internationalize. But this task does not only require central governments,Fernhaber, Li and Wu (2019) also determine that the region in which a company is located promotes its internationalization, so the role of regional governments will be equally important. In studies applied in Latin America,Rahko (2016) andArbix, Salerno and De Negri (2010) found that efforts to strengthen institutions and to improve international competitiveness have produced good results in the region. Among the actions taken,Brenes, Camacho, Ciravegna and Pichardo (2016) highlight that the lowering of trade barriers has led companies from Chile to internationalize; trade opening generated a series of changes in the countries of the region from legislation (evidence of transformations in the regulatory pillar), a change in the country's business network, rethinking the company's vision of global markets (normative pillar), to the adaptation and improvement of the knowledge available to implement strategies of all kinds within companies (cognitive pillar).

Likewise,Galindo, Méndez and Alfaro (2010) consider innovation as an instrument used by companies that allows them to enter new markets or increase their share in those in which they already operate, thanks to the added value given to the products and services offered.Bagheri, Mitchelmore, Bamiatzi and Nikolopoulos (2018) mention that technological innovation makes it possible to achieve superior performances abroad, demonstrating such positive effect.Hsieh, Child, Narooz, Elbanna, Karmowska, Marinova, Puthusserry, Tsai and Zhang (2019) also find that the innovation strategy adopted by the company influences the pace and speed of deepening of the internationalization process.

On the other hand, types of innovation have also addressed as important drivers of internationalization.Cassiman, Golovko and Martinez-Ros (2010) find that a type of innovation such as product innovation improves the average probability of entering export markets by 49%, just as it improves the performance of the company, as observed byRamadani, Hisrich, Abazi-Alili, Dana, Panthi and Abazi-Becheti (2018).Lamotte and Colovic (2013); andMartínez-Román, Gamero, Delgado-González and Tamayo (2019) also highlight the favorable effect of product innovation on internationalization adding that if product and process innovations (new technologies in production) are combined, the possibility of internationalization increases. Beyond the type of innovation, the object of innovation is also a relevant element when internationalizing a company; for example,Hojnik, Ruzzier and Manolova (2018) determine that eco-innovation, represented in innovations that allow companies to obtain environmental sustainability, has a positive effect on internationalization.

Zivlak, Ljubicic, Xu, Demko-Rihter and Lalic (2017) also find that innovations are positively influenced by internationalization due to direct contact with foreign customers, the search for profits and increased competitiveness in new markets. This shows that not only innovation influences internationalization, as mentioned in the previous paragraph, but also there is a positive effect of internationalization on innovation, demonstrating the existence of a virtuous circle.Genc, Dayan and Faruk Genc (2019) determine that all international experiences do not generate positive effects on innovative performance, being necessary that internationalization leads companies to a greater market and entrepreneurial orientation in order to see favorable effects on innovation.

When analyzing some statistics on internationalization, we observe that exporting companies in Latin America are barely 1% of existing companies, where only 10% of SMEs in the region are involved in foreign trade processes compared to 40% of their European counterpart, according to Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean (ECLAC, 2016). At the country level, the 2018/2019 GEM report highlights that while the internationalization rate (measured by the percentage of companies selling more than 25% to foreign clients) in countries such as Colombia and Panama is close to or above 10% (9.6% and 14.4%, respectively), in other countries such as Brazil this rate stands at 0.3%. Regarding the gender of the entrepreneur,Chen, Saarenketo and Puumalainen (2016) in a study applied in six South American countries, find that women entrepreneurs are less likely to establish international companies than their male counterparts. Among the main explanations of this result is the difficulty of access to resources in financial institutions (MasTur & Simon Moya, 2015). On the latter,Guzman and Kacperczyk (2019) report that in California and Massachusetts female-led companies are 63% less likely to obtain external financing than maleled companies. The differences found in data on the degree of internationalization between regions, countries and the gender of the company leader, show the need to improve the institutional frameworks through policies and programs that promote internationalization, or that promote innovation by achieving a subsequent favorable effect on internationalization.

After presenting some concepts about institutions, the way in which they can positively influence the level of entrepreneurship, innovation and internationalization of a country and the existence of the virtuous circle, we now present a section of recommendations based on theory review and we propose possible areas of institutional improvements in which countries and companies can accomplish.

4. Recommendations for improvements to the institutional framework

The work of previous authors is a starting point for improvement of the institutional framework that can be applied in a country. There are several factors to be considered, for example,Zhang et al. (2017) consider that government support as an essential tool for companies to deal with market uncertainty, inasmuch as protecting property rights motivates companies to invest and improve capabilities in innovation. In addition to the protection of property rights,Boudreaux (2017) considers that without profit opportunities, entrepreneurs lack incentives to innovate, and aspects such as bureaucratic procedures and corruption become problems. On bureaucratic procedures,De Soto (2000) hightlights that while in the US a new company needs few days or weeks to open a new business, 300 days are needed in Peru and 379 days are needed in Tanzania. With relation to corruption,Peng, Wang and Yi (2008) find that corruption becomes a major challenge for companies that want to internationalize, so transparency issues will improve their chances; however, even with a transparent scenario, there are still some limitations where the institutions, through their three pillars, can act.

First, access to resources is a key issue because having financial support makes it easier for businesses to innovate and internationalize (Zhang et al., 2017).Coad, Segarra and Teruel (2013) conclude that as companies grow the weight of external financial sources steadily decreases, leveraging investments in capital being accumulated. Therefore, the financing policies (regulatory pillar) to be applied in a country should have young companies as their main benefactors. Moreover, positive discrimination is required for women when accessing resources, according toMasTur and Simón Moya (2015), andGuzmán and Kacperczyk (2019). To conclude,Liu and Ko (2017) find that non-financial companies that have a strong relationship with a bank present a higher probability of internationalizing, thus requiring a business culture better associated with banking entities (normative pillar).

When governments establish institutional frameworks that facilitate the generation of technologies and human talent, the efficiency and effectiveness of companies' operations increase. When the above situation occurs, countries are more likely to innovate and, at higher levels of economic development and in the presence of innovation-driven economies, the gender gap tends to narrow (Sarfaraz, Faghih & Asadi, 2014). Therefore, implementing new policies and improving the existing ones associated with the cognitive pillar (widely shared degree of education) will favor the presence of women. Government support can also be technical, for example,Özsungur (2019) shows that in Turkey 69.5% of entrepreneurs required advisory support for their businesses, ranging from advice on starting a business to advice on exporting; therefore, actions must also be taken in this area.

A topic that is increasingly important is the relationship between universities and companies.Yip and Mckern (2014) find that the company-university relationship is one of the R+D enablers that, as already shown, has a positive relationship with innovation. It is necessary to make the most of universities as innovation ecosystems; therefore,Fisher, Salati and Rücker (2019) establish that it is necessary to generate normative frameworks that promote and facilitate their links with companies. Among other advantages of this relationship,Çingitas and Ecevit (2015) find better quality workforce and efficiency in creating new projects that universities can provide to companies.

Moreover, the theoretical results of this paper strongly support the introduction of a new type of economic policy in which the promotion of internationalisation and innovation would be simultaneously targeted at the level of a company in order to efficiently increase the competitive potential of an economy.

Finally, depending on the conditions of each country, as described in their institutional profile, differential policies can be applied to overcome institutional weaknesses. In the academic literature, authors recommend applying policies to a specific type of company.Roelfsema and Zhang (2018) state that smaller companies should be supported primarily as they can leverage their low-cost capabilities in internationalization and leave it to larger companies to grow in the domestic market (faster growth). In contrast,Lederman et al. (2014) recommend that policies should shift from an SME-centric approach to one focused on young companies regardless of size.Giraudo, Giudici and Grilli (2019) also focus on young companies, especially those that are young and innovative.Knight and Cavusgil (2004) stipulate that the companies to be prioritized are the born-global firms since they seek superior returns in international business at or near their founding. Finally,Arbix, Salerno and De Negris (2010), in a study applied in Brazil, consider that governments should support companies that promote technological innovation, since they have a better workforce and add value to exported goods, thus they are more competitive.

Regardless of the type of company, what should prevail in the policies to be implemented through the three pillars is the promotion of innovation and internationalization. When institutional frameworks favor innovation, productive processes and the quality of the products and services to be offered are improved and thus companies gain competitiveness and contribute to the creation of jobs, economic growth and the survival of the industry. In addition, when companies innovate, they are more likely to internationalize, which also contributes to economic development of the country.

5. Conclusions

As emphasized fromCoase's (2009), adequate institutions are needed for a market economy to be feasible. Promoting an adequate institutional framework will make it easier to resolve transactions, promote entrepreneurial orientation (Dickson & Weaver, 2008), and allow for external stability (Bucelli, Costa Neto & Vendrametto, 2014). The aspects mentioned above are important because if achieved, companies will have the best external environment to innovate and internationalize. To make the appropriate improvements to the institutional framework, actions can be taken through three dimensions: (i) the regulatory dimension, which is associated with policies, laws and norms, for instance, facilitating access to resources for SMEs; (ii) the normative dimension, which is related to social norms, beliefs or values, for example, valuing entrepreneurship and innovation in a society; (iii) and finally, the cognitive dimension, which is linked to widely shared knowledge and higher levels of education.

In addition, it is necessary for the institutional framework to promote entrepreneurship since it is inside the company where innovation and internationalization are mainly developed. Institutional frameworks that influence greater investments in R+D, promote competition among companies and the generation of patents, will succeed in increasing levels of innovation, which translates into higher productivity, economic growth and increased employment (Kijek & Kijek, 2019). The institutional framework, as well, influences the international strategy adopted by a company. Internationalization is also promoted by higher levels of innovation, which in turn are influenced by internationalization, since international companies need to continue innovating in order to remain abroad and thus evidencing the advantages of virtuous circle.

Finally, specific actions to improve institutional frameworks and take advantage of the positive effects of the virtuous circle in a country include the following actions: policy makers should work on reducing bureaucratic procedures for companies, increasing transparency in the economy, promoting the generation of technologies and skilled human capital, improving the link between companies and universities (these are enablers of R+D and have a quality workforce), facilitating access to resources for companies and providing technical support.

This study addresses new research directions and encourage other researchers to analyze the moderating role played by institutions in entrepreneurship, innovation and internationalization. It is necessary to increase our knowledge about how countries must build or restructure their institutional frameworks to take advantage of the positive effects of these activities on the economy. At a firm level, innovation strategy should be an integral part of a corporate strategy and the complex link between the two should be particularly addressed by managers in the process of internationalisation of business activities.