1. Introduction

In the current competitive environment, characterised by high levels of dynamism and complexity, the resource-based view states that a firm’s endogenous factors constitute a more solid foundation for its competitive advantages (Peteraf, 1993; Amit & Shoemaker, 1993). More precisely, according to Spender (1996), since the origin of all tangible resources lies outside the firm, competitive advantage is more likely to come from its specific intangible knowledge. Firms must generate new capabilities while simultaneously using their existing knowledge resources, hence the need for them to achieve a balance between knowledge exploration and exploitation (March, 1991).

Closely linked to the terms exploration and exploitation is a research strand which revolves around the concept of organisational ambidexterity. Broadly speaking, ambidexterity sees exploration and exploitation as being neither independent nor autonomous processes; instead, they interact on a continuous basis.

Despite firms’ need to remain competitive, they must face yet another unquestionable reality: growing globalisation which has led to practically all economic sectors having access to global markets. Multinational firms have emerged as diversified knowledge corporations, which need to coordinate knowledge creation and transfer it between different locations with the aim of capitalising on it and reaching optimal global performance. Therefore, they need to focus on knowledge integration (Frost & Zhou, 2005), which implies simultaneously performing knowledge exploration and exploitation activities inside the multinational corporation. This knowledge integration process may take place both in the parent company and in its subsidiaries, the latter acquiring key importance because they become a source of innovations and competitive advantages not only for the subsidiary itself but also for the multinational as a whole (Zhang, Jiang & Cantwell, 2015; Zhang & Cantwell, 2013; Zhang & Jiang, 2013; Bartlett & Ghoshal, 1989).

A wide variety of theoretical and empirical works focused on organisational ambidexterity can be found in the literature (O’Reilly & Tushman, 2011, 2008; Andriopoulos & Lewis, 2009; Raisch, Birkinshaw, Probst & Tushman, 2009; Rothaermel & Alexandre, 2009; Simsek, Heavey, Veiga & Souder, 2009; Jansen, Tempelaar, Van den Bosch & Volberda, 2009; Raisch & Birkinshaw, 2008; Cegarra- Navarro & Dewhurst, 2007; Birkinshaw & Gibson, 2004; He & Wong, 2004; Holmqvist, 2004; Tushman & O’Reilly, 1996); others consider the field of knowledge development and exploitation within multinationals (Morris, Snell & Björkman, 2016; Zhang & Jiang, 2013; Jensen & Szulanski, 2004; Buckley & Carter, 2004; Almeida, 1996; Foss & Pedersen, 2002; Frost, Birkinshaw & Ensign, 2002; Birkinshaw, Hood & Jonsson, 1998); and more recently, a number of papers have combined both knowledge areas (Vahlne & Jonsson, 2017; Huang & Cantwell, 2017; Reilly & Sharkey Scott, 2016, 2010; Bandeira-de-Mello, Fleury, Aveline & Gama, 2016; Zhang et al., 2015; Zhang & Cantwell, 2013; Bouzdine-Chameeva, Dupouët & Lakshman, 2011). This last group is quite small in our opinion, especially if attention is focused on the subsidiary as the level of analysis. Moreover, none of the studies mentioned define ‘ambidextrous subsidiary,’ nor do they explain how to identify the ambidextrous nature of a subsidiary.

In an attempt both to address these gaps in the literature and to further knowledge in this field, the present paper has a twofold objective. Firstly, to give a definition of ambidextrous subsidiary; and secondly, to determine if subsidiaries are ambidextrous according to their knowledge exploration level, the role that they play within the multinational corporation and their international competitive strategy. To achieve the proposed aims, five research questions were posed, the responses to which stemmed from the results of a quantitative study on a sample comprising 102 Spanish subsidiaries of foreign multinationals belonging to knowledge-intensive sectors. A survey with questions of several types was used in order to explore and describe the level of ambidexterity of the analysed subsidiaries.

This research makes theoretical and empirical contributions, providing a definition of ‘ambidextrous subsidiary’, establishing the foundations to determine the ambidextrous nature of subsidiaries, and applying a quantitative methodology to obtain the findings of the study.

The paper is structured as follows. After the introduction, a review of the literature on the topic of organisational ambidexterity is conducted, highlighting the ambidextrous nature of multinational corporations and laying down the theoretical foundations that permit the identification of ambidextrous subsidiaries. The methodology used, the population studied and the process of data collection are subsequently described, the results being discussed afterwards. The paper will finish with a summary of the most relevant conclusions, its contributions and potential future avenues of research.

2. Literature review

2.1 Organisational ambidexterity

Despite the fact that it is considered a highly ambiguous term and that no consensus has yet been reached in relation to its meaning (Raisch et al., 2009; Simsek et al., 2009; Raisch & Birkinshaw, 2008), various studies related to organisational ambidexterity are available in the literature. Organisational ambidexterity relates to the terms ‘exploration’ and ‘exploitation.’ For March (1991), exploration and exploitation constitute two different aspects of organisational learning. The former makes it possible to create knowledge, in which context learning takes place as a result of a process of experimentation. The latter seeks efficiency instead, applying existing knowledge to alternative uses and generating an adaptive kind of learning, mainly based on repetition (Ode & Ayavoo, 2020; O’Reilly & Tushman, 2008; March, 1991). In turn, Holmqvist (2004) sees exploration and exploitation as two interdependent processes, exploration being a prerequisite for exploitation. Nevertheless, the benefits of exploration will depend on the amount of knowledge accumulated and learned through exploitation.

Exploration and exploitation require different structures. This explains why firms will only be able to achieve long-term strategic success if they possess both the capability to operate in existing markets and the skills to combine and reshape organisational assets and structures, adapting them to emergent markets and technologies (O’Reilly & Tushman, 2008). This led us to reflect on the relevance of dynamic capabilities, which highlight the need for firms to alter their resource and capability base for the purpose of generating new value-creating strategies, so that they can adapt to the ever-changing environment and remain competitive over time (Helfat et al, 2010; Wang & Ahmed, 2007; Eisenhardt & Martin, 2000).

March (1991) claims that both processes -i.e. exploration and exploitation- are necessary in an organisation, which needs to reach an appropriate balance between them. The concept of ambidexterity arises from this idea, with an ambidextrous organisation being one which can simultaneously and successfully undertake knowledge exploration and exploitation (O’Reilly & Tushman, 2013, 2011, 2008; Tushman & O’Reilly, 1996).

In the view of O’Reilly and Tushman (2008), dynamic capabilities lie at the core of a firm’s ability to be ambidextrous and to compete in mature as well as emergent markets at the same time, thus achieving both exploration and exploitation. Nonetheless, they believe that the complexity and dynamism which characterises the current business environment will possibly make it necessary to have separate units, with different business models and alignments for each, so that exploitation and exploration can be simultaneously carried out. These separate units would move guided by a common strategic purpose and by a set of values which would allow the organisation to capitalise on shared assets. Such is the case of multinational firms.

2.2 Organisational ambidexterity in the subsidiaries of a multinational corporation

Strategies in the multinational context pursue a joint development of knowledge that will subsequently be shared globally. This not only stresses the importance increasingly assigned to subsidiaries as a source of knowledge but also highlights changes in the literature on multinationals, which has traditionally focused on the parent company as the unit of analysis and the source of competitive advantages which are later implemented in its subsidiaries. Attention has been moving towards the latter in recent years, because subsidiaries often own internal capabilities that become a source of innovations and competitive advantages, not only for the subsidiary itself but also for the multinational as a whole (Oh, Li & Nguyen, 2015; Ho, 2014; Cantwell & Mudambi, 2005; Rugman & Verbeke, 2001; Bartlett & Ghoshal, 1989).

However, almost no publications have linked ambidexterity and subsidiaries. Two of those that do are studies by Reilly and Sharkey Scott (2010, 2016). In the former, the authors adopt a subsidiary level of analysis to propose a theoretical model on how subsidiaries can use their capabilities and knowledge to build bargaining power. In the latter, the authors explore how subsidiary units balance and negotiate allegiances within a modern multinational context. Both consider ambidexterity not as an outcome for the subsidiary but rather as a critical means of survival. Other studies discuss these topics from a general point of view. Thus, Huang and Cantwell (2017) explore how multinationals address uncertainty by valuing local ambidexterity when making decisions related to foreign direct investments; Bouzdine-Chameeva et al. (2011) examine ambidexterity initiatives in multinationals without referring to the subsidiary as a level of analysis; Bandeira de Mello et al. (2016) study the ambidexterity implementation process during the internationalisation of emerging market multinationals; and Vahlne and Jonsson (2017) analyse ambidexterity as a dynamic capacity within the framework of multinational globalisation.

None of the aforementioned research provides a definition of an “ambidextrous subsidiary”, nor determines how to identify if a subsidiary is ambidextrous. The theoretical bases required to address these gaps identified in the literature will be established below.

Those subsidiaries which are forced to create or acquire knowledge because of circumstances associated with a particular market or sector will formulate exploration strategies, acquiring or developing the knowledge that they need internally or externally (from their multinational corporation or from the local environment in which they are located). Instead, subsidiaries owning valuable knowledge which can be used for other multinational units will most probably undertake exploitation strategies, thus becoming a source of knowledge for the rest of the organisation.

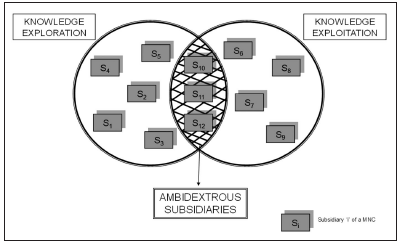

In accordance with these ideas and on the basis of the above theory of ambidexterity, it will be considered that the subsidiary of a multinational is ambidextrous when it can undertake knowledge exploration and exploitation in a simultaneous manner. Expressed differently, the conception of an ambidextrous subsidiary presents the latter as being able not only to internally or externally develop or acquire -i.e. to explore- knowledge which proves valuable both for itself and for the rest of its corporation, but also to act as a source of valuable knowledge -i.e. to exploit it- for other multinational units (Figure 1).

Several arguments can help to know the degree of ambidexterity achieved by the subsidiaries of a multinational.

Firstly, four types of strategies to explore knowledge can be distinguished following Rosenkopf and Nerkar (2001), namely: internal exploration; external exploration, local exploration; and radical exploration. By means of internal exploration, the subsidiary develops and/or acquires new knowledge exclusively considering the knowledge available in other areas of its multinational corporation. In turn, external exploration allows the subsidiary to acquire from the local environment very similar knowledge to that which it already possesses. As for local exploration, it implies that the subsidiary has achieved almost complete autonomy when it comes to creating knowledge, developing knowledge which is very similar to that which it already possesses, but without using existing knowledge, neither in its business environment nor in other subsidiaries. Finally, radical exploration enables the subsidiary to acquire new knowledge coming from the external context in which it develops its activity, which differs both from the knowledge available to the subsidiary itself and from that owned by the other multinational units.

Secondly, according to the dimensions ‘degree to which the subsidiary receives knowledge from the rest of the corporation (knowledge inflow)’ and ‘degree to which the subsidiary supplies knowledge to the rest of the corporation (knowledge outflow),’ Gupta and Govindarajan (1991) argue that the subsidiaries of a multinational can play four different roles: global innovator; integrated player; implementer; and local innovator. When the subsidiary has achieved self-sufficiency in terms of knowledge development and acts as a source of knowledge for other units -receiving hardly any knowledge from the rest of the multinational- it adopts the role of a global innovator. When the subsidiary acts as a source of knowledge for other units but simultaneously needs a high volume of knowledge coming from the rest of the multinational, it tends to assume the role of an integrated player. If the subsidiary is largely dependent on the knowledge owned by other corporation units and provides hardly any knowledge to the rest of the organisation, it will most probably play the role of an implementer. Finally, when the subsidiary develops the knowledge that it needs and does not receive any knowledge nor supply it to other multinational areas, it adopts the role of a local innovator.

Thirdly, the international competitive strategy chosen by a multinational is also bound to influence the knowledge exploration and exploitation tasks that it performs. Based on the classification made by Bartlett and Ghoshal (1989), the subsidiary tries to achieve local sensitivity using a multidomestic strategy, creating the knowledge needed to meet the local demands which is not then transferred to the rest of the multinational. In a global strategy, knowledge development is confined to the parent company, which will be transferred to each one of the subsidiaries in the form of goods and services for their subsequent exploitation. For an international strategy, the need for subsidiaries to adapt the outputs generated in the parent company to local preferences will require a minimum of knowledge development in order for those outputs to be exploited. In contrast, a transnational strategy offers greater opportunities when it comes to achieving simultaneous knowledge exploration and exploitation within a single subsidiary. In this case, knowledge exploration may take place both in the parent company and in its subsidiaries, that knowledge being subsequently transferred across the multinational so that it can be exploited in each and every corporate area. As can be seen, the influence of organizational culture and absorption capacity on the intra-organizational tacit knowledge transfer will be a central issue in matters of ambidexterity (Máynez-Guaderrama, Cavazos-Arroyo & Nuño-De la Parra, 2012).

Taking the theory described above as a reference and considering the aims set out in this study, the following research questions were put forward: (1) Are subsidiaries based in Spain knowledge explorers? (2) If they are, which knowledge exploration strategy do they most identify with? (3) According to intra-corporate knowledge flows, which role do they play inside the multinational? (4) Does any coherence exist between the role played by subsidiaries and their international competitive strategy? (5) In light of all the above, can subsidiaries based in Spain be considered ambidextrous organisations? The coming sections will try to provide answers for these research questions.

3. Methodology

An empirical study was carried out using a quantitative methodology. The main reason for the choice of such a methodology lies in the fact that most of the research focused on the topics under consideration is either theoretical or case-study-based (Vahlne & Jonsson, 2017; Bandeira de Mello et al., 2016; Bouzdine-Chameeva et al., 2011; Reilly & Sharkey Scott, 2010). In addition, the aim of this study consists not only in answering the proposed research questions but also in ensuring a subsequent generalisation of the results obtained.

3.1 Sample and data collection

The population to be studied consisted of Spanish subsidiaries of foreign multinationals belonging to knowledge- intensive sectors. The definition of knowledge-intensive sectors followed the classification developed by the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development - OECD (2001). Depending on their technological level, high-tech manufacturing sectors, medium-high technology and knowledge-intensive services are regarded as knowledge-intensive sectors. The decision to place the focus on the subsidiary in lieu of the parent company finds its justification in the growing importance recently assigned to the former as a source of competitive advantage for the whole multinational -as already mentioned in the previous section. Knowledge-intensive sectors characteristically own an important technological base, show ongoing development of new knowledge and make great efforts in research and development. The justification for the focus of the present study on these sectors lies in the conviction that the subsidiaries located therein are most likely to present high levels of dynamism, showing a strong commitment not only to knowledge generation but also to its exploitation as a way to cope with the pressures imposed by their business environment.

Faced with a lack of databases explicitly focussed on subsidiaries of foreign multinationals in Spanish territory, and after consulting a variety of directories, a decision was made to use SABI (the Spanish acronym for “System of Analysis for Iberian Balances”). After the removal of duplicates and inactive firms at the time of the study, the population consisted of 1,158 Spanish subsidiaries of foreign multinationals.

A questionnaire was used to collect information, which was sent to the subsidiary’s CEO or Managing Director. Questionnaire preparation went through several stages. Firstly, a thorough review of studies on knowledge management, ambidexterity and multinationals was carried out. Secondly, experts in this field discussed and reflected on the draft questionnaire, with a number of descriptive and exploratory case studies ensuing. Thirdly, a pilot test was performed which included personal interviews with the chief executives of five firms. The completion of this stage meant that the final questionnaire was ready (see Annexes).

The questionnaire was sent both via postal mail and by email. When a month had elapsed since initial contact, a second attempt was made in order to increase the response rate (Dillman, 2000). A total of 102 duly completed questionnaires arrived, which represents an 8.8% response rate. Despite that relatively low response percentage, the number of observations obtained suffice to reproduce the population’s characteristics and accordingly permit the generalisation of the results collected. The studies on non-response bias confirmed sample representativeness -indicating that the values for the variables ‘approximate number of employees’ and ‘approximate annual turnover’ lay within the same intervals (Student’s T-test was used for means comparison) for all companies, regardless of whether they had answered the questionnaire or not.

4. Results and discussion

4.1 Profile of participating subsidiaries

The firms under consideration belong to high- and medium-high-technology manufacturing sectors and to knowledge-intensive services, with a slight predominance of industrial subsidiaries (56.3%) over service ones (43.7%). Amongst the former stand out those in the chemical industry, machinery and equipment manufacture, and the automotive sector, whereas the latter have professional services, programming and technological consultancy as their most important field of activity. 43% of subsidiaries recognise that they apply a ‘transnational’ strategy, 28% follow a ‘global’ strategy, 8% opt for an ‘international’ strategy, and the remaining 21% use a ‘multidomestic’ strategy.

The subsidiaries analysed come from multinationals based in up to 15 different countries, with Germany providing the majority -23.4% of the total. 43.8% of subsidiaries had a ‘greenfield’ status, 26.2% constituted ‘joint-ventures’ and 30% were established through the acquisition of an already existing Spanish firm (‘acquisition’). Considering both turnover and number of employees, it can be said that 72.5% of the subsidiaries studied are SMEs (fewer than 250 employees), the remaining 27.5% corresponding to large-sized firms.

4.2 Research question 1. Are Spanish-based subsidiaries knowledge explorers?

According to the literature review section, three dimensions are essential when it comes identifying these strategies: (1) if the subsidiary develops and/or acquires knowledge or not; (2) the impact that the subsidiary’s internal and external context has on its knowledge development and/or acquisition; and (3) the similarity - or dissimilarity- between the new knowledge developed and/or acquired by the subsidiary and that which initially existed. The joint consideration of these three dimensions enabled Rosenkopf and Nerkar (2001) to distinguish four types of knowledge exploration strategies, namely; internal exploration, external exploration, local exploration, and radical exploration.

Three questions were included in the questionnaire for the purpose of identifying exploration strategies. Question 1 was intended to reveal if the Spanish subsidiary develops and/or acquires useful capabilities in R&D, production or marketing, both for itself and for the rest of its multinational corporation. The second question in turn tried, on the one hand, to check if the Spanish subsidiary obtains knowledge from its internal customers, suppliers and R&D units for capability development purposes; and on the other hand, to check whether the knowledge obtained is similar to or different from that which the Spanish subsidiary initially possessed. Question 3 sought to acquire the same information, albeit from the point of view of external customers, suppliers and R&D units.

Analysing the data for each case allowed us to realise that 93 subsidiaries -out of 102 studied- were performing some initiative related to knowledge development and/or acquisition in the functional areas examined, as opposed to 9 subsidiaries which explored no type of knowledge whatsoever. Table 1, which shows information regarding the knowledge exploration initiatives identified in those 93 subsidiaries, reveals the existence of 179 knowledge creation and/or acquisition initiatives -59 of them corresponding to R&D-related knowledge, 69 to production knowledge and 51 to marketing knowledge.

Table 1 Knowledge exploration initiatives

| Knowledge development and/or acquisition initiatives | Frequencies | Percentage |

| Capabilities in R&D | 59 | 33% |

| Capabilities in Production | 69 | 38.5% |

| Capabilities in Marketing | 51 | 28.5% |

| TOTAL | 179 | 100% |

Source: own elaboration.

The findings obtained lead us to state that Spanish subsidiaries of foreign multinationals are deeply engaged in knowledge exploration; a large proportion of them (93 out of 102) identify with initiatives oriented towards the development and/or acquisition of capabilities in R&D, production or marketing. Considering their nature as firms belonging to knowledge-intensive sectors, these results highlight the need for these subsidiaries to continuously update their capabilities, mainly due to the demands of the ever-changing environment in which they operate.

4.3 Research question 2. If they are, what knowledge exploration strategy do they most identify with?

The second research question can be answered by collecting information on two aspects: (1) the impact that internal and external agents have on the subsidiary’s capability development; and (2) the type of knowledge developed or acquired. Concerning the extent to which the subsidiary’s internal & external customers, suppliers and R&D units influence its development and/or acquisition of capabilities, the data reveals that internal sources of knowledge are the most often utilised. As for the type of knowledge, it has been found that subsidiaries develop and/or acquire both similar and different knowledge to that which is initially possessed (Table 2).

Table 2 Source of knowledge and knowledge similarity

| Source of knowledge | Frequency | Percentage | Similar knowledge | Different knowledge |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Internal customers, suppliers and R&D units | 63 | 62% | 49% | 51% |

| External customers, suppliers and R&D units | 39 | 38% | 48% | 52% |

| TOTAL | 102 | 100% |

Source: own elaboration.

The findings show that 62% of the Spanish subsidiaries studied develop and/or acquire capabilities through knowledge coming from other units of their multinational corporation, largely ignoring the knowledge available in the country or region where they are based. The remaining 38% of subsidiaries use knowledge from external customers, suppliers and R&D units. Following the strategies identified by Rosenkopf and Nerkar (2001), these results lead us to conclude that the strategy carried out by the subsidiaries studied tends to lie closer to ‘internal’ exploration. In other words, the subsidiary develops and/or acquires new knowledge mostly considering the knowledge available in other parts of the multinational. In contrast, 38% of subsidiaries choose to implement ‘external’ or ‘radical’ exploration strategies, both of which imply that the subsidiary develops and/or acquires knowledge coming from the local or regional environment in which it operates. The main difference lies in the type of knowledge developed or acquired, however, if the knowledge obtained is very similar to that which the subsidiary already possesses, then the strategy is defined as ‘external’ exploration. Instead, if this knowledge differs both from the knowledge available to the subsidiary itself and from that possessed by other multinational units, the strategy is referred to as ‘radical’ exploration. The former accounts for 48% of cases, the remaining 52% corresponding to the latter.

4.4 Research question 3. According to intra-corporate knowledge flows, which role do Spanish subsidiaries play inside the multinational?

Taking up the considerations made in the literature review section, Gupta and Govindarajan (1991) draw a distinction between four different roles according to the orientation of intra-corporate knowledge flows, namely: global innovator (high outflows and low inflows); integrated player (high outflows and inflows); implementer (low outflows and high inflows); and local innovator (low outflows and inflows).

The dimension “inflow of knowledge from the rest of the corporation to the subsidiary” (inflow) was measured using question four of the questionnaire, while the assessment of the dimension “outflow of knowledge from the subsidiary” (outflow) was addressed through question five.

Both questions included three items and were dichotomous. While question four asked interviewees to confirm whether the capacities developed by other multinational units in the R&D, production and marketing areas were actually used by the Spanish subsidiary, question five sought confirmation from the respondents about whether the same capabilities -albeit this time developed by the Spanish subsidiary - were used by the rest of the corporation. The comparison of outflow and inflow data for each case made it possible to obtain the roles played by the subsidiaries analysed, whose frequencies can be seen in table 3.

Table 3 Roles played by the subsidiaries under study

| Role | Frequency | Percentage |

|---|---|---|

| Global innovator | 10 | 10% |

| Integrated player | 46 | 45% |

| Local innovator | 20 | 20% |

| Implementer | 26 | 25% |

| TOTAL | 102 | 100% |

Source: own elaboration.

It follows from the preceding table that almost 50% of subsidiaries adopt the role of an integrated player. This provides evidence that nearly half of the Spanish subsidiaries analysed are responsible for emitting knowledge to be used by other multinational units (high outflows), but also that they cannot meet their own needs and require knowledge coming from the rest of the corporation (high inflows). Thanks to this role, subsidiaries make the most of the knowledge existing in any corporation area.

Conversely, the role of a global innovator is the least exercised by the subsidiaries under study. It represents 10% of the total and shows that only 10 subsidiaries are self-sufficient when it comes to developing knowledge, acting as a source of knowledge for other units and receiving hardly any knowledge from the rest of the multinational. The low number of subsidiaries with this role makes clear how necessary it is for Spanish-based subsidiaries to receive knowledge from the rest of their multinational in order to ensure self-sufficiency.

Two examples of how some of these roles can influence the exploration and exploitation of knowledge in Spanish subsidiaries of foreign multinationals can be found in the research carried out by Oltra (2012).

4.5 Research question 4. Does any coherence exist between the role played by subsidiaries and their international competitive strategy?

Following Reilly and Sharkey Scott (2016), subsidiaries must, on the one hand, prove their value by leveraging their local external knowledge base and the opportunities that it provides and, on the other hand, maintain a shared vision through an alignment with parent-driven objectives.

This statement is consistent with the idea formulated in the fourth research question. Answering it requires comparing the roles played by subsidiaries (Gupta & Govindarajan, 1991) and their international competitive strategies (Bartlett & Ghoshal, 1989). From a theoretical point of view, it is expected that the subsidiaries with the roles of integrated player, local innovator and implementer follow ‘transnational,’ ‘multidomestic’ and ‘global’ strategies, respectively. The reasons to suggest such relationships can be found below:

(1) Firstly, subsidiaries with the role of an integrated player explore knowledge on an ongoing basis, in turn serving as a source of knowledge for other multinational units, all of which matches the characteristics inherent to a ‘transnational’ strategy. Such a strategy provides the best chances to achieve simultaneous knowledge exploration and exploitation inside a subsidiary;

(2) Secondly, subsidiaries which play the role of a local innovator usually explore the knowledge that they need to succeed in adapting to their local geographical and business environment -without transferring that knowledge to the rest of the corporation. These ideas are in keeping with the ‘multidomestic’ strategy postulates;

(3) Thirdly, subsidiaries with the role of an implementer are characterised by using the existing knowledge in other multinational corporation units -without transferring almost any knowledge to others. This refers us back to the ‘global’ strategy, according to which knowledge development mainly takes place either in the parent company or in excellence centres, so that it can be later transferred in the form of products and services to each one of the subsidiaries for their subsequent utilisation.

Our findings confirm that the suggested relationships, the percentages found between the roles played by subsidiaries and their international competitive strategies are coherent (Table 4).

Table 4 Coherence between the role and the international competitive strategy

| Role | International competitive strategy | Coherence according to the theory |

|---|---|---|

| Integrated player (45%) | Transnational (43%) | Yes |

| Local innovator (20%) | Multidomestic (21%) | Yes |

| Implementer (25%) | Global (28%) | Yes |

| Global innovator (10%) | International (8%) | No |

Source: own elaboration.

Although the table shows that the proportion of subsidiaries playing the role of a global innovator largely resembles that of those which implement an ‘international’ strategy, no evidence exists of coherence between both aspects in theoretical terms. The main reason lies in the fact that subsidiaries with the role of a global innovator are self-sufficient in developing the knowledge that they need, which simultaneously serves as a source of knowledge for other multinational units. Subsidiaries embarked upon ‘international’ strategies do not follow the previous patterns, though, since the knowledge required is supplied to them from other parts of its multinational and does not become a source of knowledge for the rest of the organisation.

4.6 Research question 5. In the light of all the above, can Spanish-based subsidiaries be considered ambidextrous organisations?

Pursuant to the research proposal, a subsidiary is ambidextrous when it can internally or externally develop or acquire knowledge which not only proves valuable both for itself and for the rest of its corporation but also serves as a source of valuable knowledge for other units of its multinational.

Despite having verified from the perspective of knowledge exploration that most of the subsidiaries examined do undertake exploratory strategies, it becomes necessary to consider their roles as well as the international competitive strategies chosen by these subsidiaries in order to ascertain their ambidextrous nature.

In relation to the roles played, the fact that 45% of subsidiaries adopt the role of an integrated player stresses the high intra-corporate knowledge flows made by those subsidiaries in both directions (inflows and outflows), which in turn highlights their strongly ambidextrous nature. Nevertheless, 55% of the remaining subsidiaries cannot be said to have a high degree of ambidexterity. More precisely, 10% of subsidiaries adopt the role of a global innovator, which suggests that they generate knowledge and subsequently exploit it through its transfer to the other units of their multinational -thus wasting the knowledge from other corporate areas, since the knowledge available in other subsidiaries is simply ignored. To this must be added that 25% of subsidiaries with the role of an implementer cannot be considered ambidextrous either; despite acquiring large amounts of knowledge from other multinational units, they do not exploit their knowledge because the latter is not transferred to the rest -exactly as it happens in the case of subsidiaries which assume the role of a local innovator.

According to these findings, it can be stated that the Spanish subsidiaries analysed do not always undertake knowledge exploration and exploitation simultaneously.

5. Conclusions

The necessity of behaving as smart organisations forces firms both to be highly dynamic and to generate new capabilities, with the aim of remaining competitive in the complex environment in which they operate and while simultaneously using their existing knowledge resources. They consequently need to behave as ambidextrous organisations able to achieve a balance between knowledge exploration and exploitation. This premise, along with the growing multinationalisation of firms, led us to explore the issues associated with subsidiaries’ ambidexterity. In its attempt to address the gaps identified in the literature, this paper pursued a twofold aim: (1) providing a definition of an ambidextrous subsidiary; and (2) laying the foundations to determine if Spanish-based subsidiaries are ambidextrous according to their knowledge exploration level, the role that they play within the multinational corporation and their international competitive strategy.

A thorough review of the literature on the topics analysed led us to consider that a subsidiary is ambidextrous when it can internally or externally develop or acquire -i.e. to explore- knowledge which proves valuable both for itself and for the rest of its corporation and, at the same time, it serves as a source of valuable knowledge -i.e. to exploit it- for other units of the multinational. Five research questions were posed seeking to accomplish the second objective, the answers for which came from a quantitative study focused on a sample of Spanish subsidiaries of foreign multinationals belonging to knowledge-intensive sectors. The following statements can be made in view of the results obtained:

The Spanish subsidiaries analysed are deeply engaged in knowledge exploration, since a large proportion of them (93 out of 102) undertake the development and/ or acquisition of capabilities in R&D, production or marketing. The capabilities generated and/or acquired in production are the most numerous (38.5%).

Internal sources of knowledge are the most often used. 62% of Spanish subsidiaries use knowledge coming from other units of their multinational corporation, largely wasting the knowledge available in the country or region which hosts them (‘internal’ exploration strategy). The remaining 38% of subsidiaries use knowledge from external customers, suppliers and R&D units (‘external’ or ‘radical’ exploration strategies).

Regarding the type of knowledge developed or acquired, a balance exists between similar knowledge and that which differs from knowledge initially possessed by the subsidiary.

The comparison between subsidiaries’ knowledge outflows and inflows made it possible to know their respective roles. 45% of subsidiaries analysed adopt the role of an integrated player, while the role of a global innovator is the least exercised (10%).

The theoretical framework developed suggests that subsidiaries with the roles of integrated player, local innovator and implementer should follow ‘transnational,’ ‘multidomestic’ and ‘global’ strategies, respectively. Our findings confirmed the proposed relationships.

Assuming the role of an integrated player means that the subsidiary provides the rest of the multinational with the knowledge that they generate, and in turn receives the knowledge that they need from that same multinational. By definition, the ‘transnational’ strategy implies joint learning inside the corporation, where every unit becomes involved in creating useful knowledge and exploiting that coming from other units. Based on these ideas, only subsidiaries with integrated player roles and ‘transnational’ strategies can be seen as ambidextrous. Despite mostly favouring knowledge exploration, the Spanish subsidiaries analysed do not simultaneously exploit their knowledge. This mainly has to do with the role that they play inside the multinational, together with the international competitive strategy formulated by the parent company. From this research point of view, only about 50% of the subsidiaries examined are ambidextrous, showing coherence between the role as an integrated player and their ‘transnational’ strategies. The remaining subsidiaries do not seem to be important as generators of valuable capabilities for the other corporate units. The latter may be suffering from ‘myopia of learning’ and ‘not-invented-here syndrome,’ which would prevent them from receiving capabilities originating in other multinational areas. Within a ‘myopia of learning’ context (Levinthal & March, 1993), firms essentially draw upon the internal knowledge obtained from their own experience, focusing to a greater extent on immediate knowledge (what they can do) than on valuable knowledge existing outside. As for the “not-invented-here syndrome” (Gupta & Govindarajan, 1991), this refers to subsidiaries being reluctant to acquire knowledge from other units, a considerable obstacle for communication between different multinational areas.

This study makes several contributions. From a theoretical point of view, a link has been established between the theoretical approaches to the knowledge-based view of the firm, organisational ambidexterity and the multinational firm. It provided a definition of ambidextrous subsidiary, and determined if Spanish-based subsidiaries are ambidextrous according to their knowledge exploration level, the role that they play within the multinational corporation and their international competitive strategy. It must be stressed that the level of analysis in this paper moves from a parent-driven approach to one focused on the subsidiary. Empirically speaking, a quantitative exploratory study was carried out to show the extent to which Spanish subsidiaries of foreign multinationals are ambidextrous, identifying the formulas that they utilise to explore and exploit their knowledge. Most of the studies available in the literature so far have followed a case-study-based qualitative methodology. This paper additionally stresses the fact that a subsidiary’s ambidexterity level is closely linked to the role that it assumes inside the multinational, as well as to its international competitive strategy. In managerial terms, this work sheds light on how to succeed in making the subsidiaries of a multinational ambidextrous, highlighting the importance which must be assigned to the simultaneous exploration and exploitation of knowledge and how this can help to improve the competitiveness of the multinational firm as a whole. This study not only allows managers to know the alternative mechanisms which they can use to achieve that aim but also to become aware of the fact that their degree of responsibility inside the multinational, as well as the international strategy implemented by the latter, will determine its degree of ambidexterity.

Despite the contributions made, the present work is limited by its status as the first stage of a broader study; hence its exploratory and descriptive nature. Nonetheless, it seems appropriate to continue working along this line of research, trying to identify and analyse those variables through which the subsidiaries of a multinational tend to be more or less ambidextrous, applying a more advanced methodology and looking for the reasons which lead them to reach a greater or lesser degree of knowledge exploration and/or exploitation.