1. Introduction.

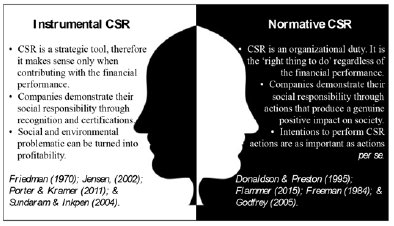

Since its origin, the overall concept of corporate social responsibility (CSR) has fluctuated between two extremes. One is the instrumentalist approach that reduces organizations’ responsibility to the procurement of the greatest possible profit for their owners (e.g., Friedman, 1970; Jensen, 2002; Sundaram & Inkpen, 2004). The other is the normative approach that extends organizations’ responsibility to those actions and decisions that ought to be performed, just because it is ‘the right thing to do’ and because they create a beneficial impact on society (e.g., Donaldson & Preston, 1995; Freeman, 1984; Godfrey, 2005). The above, beyond a merely semantic debate, represents the origin of a strong paradox that underpins a way for understanding management from both theoretical and practical angles (Cornelius, Todres, Janjuha-Jivraj, Woods, & Wallace, 2008).

In this regard, the present work examines how that paradox behaves in organizations initially conceived to create both a financial and societal impact at the same time. In this way, and taking advantage of their sense of belonging, the present work attempts to understand how highly identified members of a social business (SB) tend to label the concept of CSR, as they appreciate it according to their working experience. In order to accomplish the latter, this study is framed by the normative/instrumental dispute regarding the CSR framework and uses the organizational identification (OID) concept as a means to engage research subjects and collect valuable information.

To process the data, this work relies on artificial intelligence (AI) tools by generating a text mining analysis using a bisectional K-means (B-kmeans) method programmed in R (Yu, Jannasch-Pennell & Digangi, 2011). Data comes from 34 structured interviews conducted with an equal number of highly identified employees from a mid-sized micro-finance institution in Colombia. Results reveal homogeneity in the answers collected, and simultaneously suggest that this type of employee usually trusts the implementation of the social purpose of their particular SB. Furthermore, the study identifies two distinct clusters of employees according to their conceptions of CSR: a small cluster with a normative orientation and a more numerous one with an instrumental emphasis. The findings suggest that, although both notions of CSR are allowed to coexist in an SB indicating complementarity, its employees can also assume (ergo undertake) their primary purpose as purely business-driven (instrumental CSR), instead of societally driven (normative CSR).

Taking into consideration that more work acknowledging the salience of CSR in SBs is still needed (Littlewood & Holt, 2018; Spence, 2016), the contribution of this work is threefold. First, it aims to enhance the CSR body of knowledge, insofar as it can provide evidence to demonstrate that an unbalanced coexistence between instrumental and normative visions of the CSR can be legitimate, even among highly identified employees belonging to purpose-driven companies. In that order of ideas, this work claims that considering the nature of the business examined, instead of a probable defeat of the moral concept of the CSR, the discovered prevalence of the instrumental notion has the potential to represent a situation in which both views emphasize each other’s qualities. Second, from a practical point of view, the present work contributes to the organizational behavior domain to help disentangle how different conceptions of CSR can be visualized as correlated elements of positive individual attitudes and behaviors in SBs. Finally, this work attempts to introduce a novel methodological approach for studies in the fields of organizational theory and social enterprises.

The paper has four sections. The first section contains a brief theoretical background. The second presents, in a didactic fashion, the methodological approach utilized. The third section introduces the results obtained. Lastly, the fourth section contains, by way of conclusions, a final discussion of those results, highlighting implications, contributions, limitations, and proposed future research paths.

2. Theoretical background.

The present section is divided into three sub-sections. First, it examines the current conception of CSR and its relationship with OID. Second, it introduces the normative/ instrumentalist tension in visualizing CSR. Finally, it defines SBs in light of the notion of CSR.

2.1. Corporate social responsibility and its link with organizational identification.

From an organizational perspective, CSR has been lately associated with feelings, expressions, and actions performed by an entity (namely an organization) and for which that entity is held responsible (Jones & Rupp, 2017). However, its general conception has remained somewhat intangible and focused on something beyond just a reactiveness perception. CSR is indeed a multi-level, multi-faceted and dynamic construct, which contemplates the actions and decisions of all actors at several levels of analysis (i.e., institutional, organizational, and individual) (Aguilera, Rupp, Williams, & Ganapathi, 2007; Aguinis & Glavas, 2012). Consequently, for the sake of the present study, CSR will be defined as “context-specific organizational actions and policies that take into account stakeholders’ expectations and the triple bottom line of economic, social and environmental performance” (Aguinis, 2011, p. 855).

CSR’s theoretical domain has been broad and useful in the relevant literature, specifically through its different applications in the field of industrial and organizational psychology (Aguinis & Glavas, 2012). In this matter, one of the most fruitful research fields encompasses the perceptions of employees toward the different expressions of the concept of CSR in search of favorable organizational attitudes (Glavas, 2016). Particularly, CSR’s role has mainly been pinpointed as an antecedent of certain attitudes and behaviors on individuals (Rupp & Mallory, 2015). One of the most representative of those attitudes corresponds to the employee’s OID, which, from the theoretical point of view, is considered a robust concept directly derived from the employees’ affective commitment scholarship (Mael & Ashforth, 1992). OID is then understood as “the perception of oneness with or [belonging] to an organization” (Jones & Volpe, 2011, p. 416). Thus, employee’s OID embodies a notion at the individual level that emerged from the field of organizational behavior and can also be expressed as a specific form of social identification where an employee’s identity is derived from his/her classification into social categories, or social groups (Mael & Ashforth, 1992).

In this sense, it has been widely demonstrated that the perception that employees have on the CSR performed by the organization to which they belong influences their sense of OID (Jones & Rupp, 2017). Studies such as the ones presented in table 1 are just a few examples of the relationship mentioned above. Through their works, these authors elucidate how OID effectively became an outcome of the CSR in several contexts and circumstances. In every case, the role of employees’ perceptions has been fundamental for reaching relevant conclusions. Nevertheless, studies so far, have mainly been conceived under quantitative approaches and have been characterized by the use of different methods of operationalizing the concept of CSR at firm level, and the same notion of OID at the individual level (Aguinis & Glavas, 2013; Rupp & Mallory, 2015). Hence, only a few attempts in the qualitative domain are found (e.g., McShane & Cunningham, 2012), which suggest that this approach is yet to be adequately exploited in order to obtain new knowledge in a more focused fashion.

Table 1 Summary of the experiment

| Reference | Findings |

|---|---|

| Jones (2010) | • CSR influence organizational attitudes like retention, in-role performance, and organizational citizenship behaviors. • CSR initiatives (such as social voluntarism) are positively related to OID. |

| Kim, Lee, Lee, & Kim (2010) | • A better performance of CSR initiatives can lead to a way of maintaining a positive relationship with their employees. • CSR positively affects OID, and influence other variables like employee’s commitment. |

| McShane & Cunningham (2012) | • Employees can differentiate between authentic and inauthentic CSR programs. • The latter reasoning influences their perception of the organization. • Perceived authenticity can lead to positive outcomes such as OID and employee connections. |

| Korschun, Bhattacharya, & Swain (2014); | • The relationship between management support for CSR and OID is positive and moderated by CSR importan ce to the employee. |

| Lamm, Tosti-Kharas, & King (2015) | • Perceived organizational support toward the environment (POS-E) is associated with employees’ organizatio nal citizenship behaviors toward the environment, as well as to several job attitudes. • POS-E is positively related to OID for employees who value environmental sustainability. |

| Farooq, Rupp, & Farooq (2016) | • External CSR enhances perceived prestige whereas internal CSR enhances perceived respect. • Both external and internal CSR influence OID, but with different ways of impacting employee citizenship. • Relationships vary in strength, due to individual differences in social (local vs. cosmopolitan) and cultural (individualism vs. collectivism) orientations. |

| Hameed, Riaz, Arain, & Farooq (2016) | • The effects of perceived external and internal CSR are related to OID through two different mechanisms: perceived external prestige and perceived internal respect. • Calling orientation (i.e., how employees see their work contributions) moderates the effects induced by these forms of CSR. |

| Gils, Hogg, Quaquebeke, & Kni ppenberg (2017) | • OID and moral identity increased moral decision-making when the organization’s climate was perceived to be ethical. |

| El Akremi, Gond, Swaen, De Roeck, & Igalens (2018) | • Affected by the mediation role of organizational pride, there is an indirect relationship between CSR and OID. • The latter phenomenon occurs over and above the relationship with overall justice and ethical climate per ceptions. |

Source: own elaboration.

2.2. Instrumental CSR vs. Normative CSR.

One particular sign of the conceptual versatility of the CSR concept is its tendency to be treated as a “body with two sides”. Several valid approaches have been suggested to examine its complex nature, from both academic and practical perspectives. Some of the most relevant examples are: a) the complementarity between the internal and the external perception of CSR (Brammer, Millington, & Rayton, 2007); b) the idea of CSR as both an implicit and explicit notion (Matten & Moon, 2008); c) the embedded versus the peripheral constitution of CSR (Aguinis & Glavas, 2013); d) the tension between symbolic and substantive CSR (Tetrault-Sirsly, 2012); e) the contrast between reactiveness and pro-activeness in the method of implementing CSR (Groza, Pronschinske, & Walker, 2011); and f) the dichotomy between the instrumental and the business vision of this concept (Aguilera et al., 2007; Amaeshi & Adi, 2007; Swanson, 1995). The latter being the approach utilized in the present work.

Precisely, the instrumental/normative debate of the CSR is guided by two different forms of logic (Figure 1). On the one hand, Instrumental CSR attempts to convince companies that acting in a socially responsible way contributes to superior financial performance. The fundamental concept is that social problems can be turned into profitable business opportunities and that business organizations can achieve superior financial returns by being socially responsible (Porter & Kramer, 2011). Normative CSR, in turn, takes a different approach and relies on a moral background, particularly inviting companies to do what is morally or ethically “right” in order to be aligned with sustainable development goals. Most scholars working in this field have been identified with universal and disinterested corporate responsibilities and practices that can be implemented by companies (Scherer & Palazzo, 2007).

In their work, Amaeshi and Adi (2007) state that it is almost compulsory that CSR has had “to be reconstructed in an instrumental linguistic praxis to be meaningful to managers in their day-to-day pursuits of organizational goals and objectives” (p. 3). In this sense, much of the managerial literature promotes the ‘business case’ for CSR, which mainly declares that CSR can be useful for business. Nevertheless, it is claimed that an absolute defense of the latter perspective would only imply making ethical decisions if (and only if) it is lucrative to do so, while a more normative perspective of performing CSR suggests acting under ethical value-driven principles in any moment and under any situation (Gond & Matten, 2007). In other words, that under a pure instrumentalist approach, organizations would have the license to be committed to CSR as little as possible.

With voices for and against, it is clear that the interplay between the two approaches seems to be used to suit different contexts or audiences in order to conceptualize CSR. However, with a normative understanding of ethical business informing instrumental purposes, and with instrumental arguments that claim to achieve normative goals, the mentioned mismatch has become a problem of perceptions (Marais, 2012). This work argues that those perceptions actually represent a deontological tension in management, which ultimately is transmitted to employees.

Specifically, the word “deontology” “is a neologism coined from the Greek deon, deont: that which is binding, needful, right, proper” (Louden, 1996, p. 571). It is defined as the theory or study of moral obligation (Merriam-Webster. com, n.d.). In deontology, the end state of moral action is the very performance of it. Therefore, framed in the present work’s approach it can be said that, from a deontological perspective, CSR intentions are just as crucial as CSR actions themselves.

2.3. Social businesses and their corporate social responsibility.

The last number of years has witnessed a growing interest in the way some companies can be seen as carriers of both financial and social objectives at the same time. That is why, in order to identify a business as a social one, it is necessary to understand how the real notion of an SB covers multidimensional meanings. For instance, Ogliastri, Prado, Jäger, Vives and Reficco (2015) suggest that the concept of SB, in essence, is the result of contributions from diverse views like non-profit organizations, social entrepreneurship, inclusive business, with, of course, the concept of the CSR. That is why the very analysis of SBs brings to light their conflictive nature, which is present in both the literature and at the workplace (Doherty, Haugh, & Lyon, 2014).

In that order of ideas, significant research opportunities have been addressed for these particular themes. Firstly, it is argued that research on SBs has lagged behind its practice, especially when attempting to create a link with the CSR domain at the organizational level (Littlewood & Holt, 2018). Second, it has been determined that when referring to SB as a theoretical concept, existent literature is currently considered “incomplete if they are disregarded when theorizing CSR” (Spence, 2016, p. 46). Moreover, lastly, there have been several calls from scholars for a greater consideration of issues such as the extent to which SBs are complemented by their CSR policies and actions (Choi & Majumdar, 2014).

That is how, despite the existence of several academic approaches to these topics, an SB is generally conceived of as an economic system of “activities with a priority aim of social value creation” (Ogliastri et al., 2015, p. 168). Interestingly, the convergence point of this concept rests on the idea that, although perceived to create both financial and societal impact simultaneously, the primary objective of SBs is precisely to have a social impact, rather than to make a profit for their owners (Defourny & Nyssens, 2012). As a consequence, and in direct line with Cornelius et al. (2008), it is ideally suggested that, far from being considered either a mere strategic choice (i.e., instrumental) or a pure selection of attachment to a moral perspective (i.e., normative), the concept of CSR among SBs should be always reasonably poised between these two perspectives. Similarly, we can also imply that the individuals with predominance in experimenting and manifesting such CSR orientation are precisely those with an elevated sense of compatibility with the organization at issue, and therefore those with higher levels of OID.

Therefore, and taking into account the previously addressed issue the present work hypothesizes that according to the perception of their most committed employees, there is no predominant concept of CSR in SBs. The latter means that there would be a reasonable equilibrium between the numbers of some of the most highly identified employees following both the normative and the instrumental nature of the CSR at any given SB. In order to tackle this, the present work utilizes a single intra-organizational explorative analysis implemented at the individual level. The study performed consisted of a linguistic analysis of interviews, by using techniques derived from AI (more precisely, clustering techniques). A more detailed explanation is presented as follows.

3. Methodology.

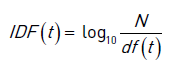

The implemented methodological process has four major stages related to text mining and content analysis. The first stage covers the dataset construction; the second stage condenses the activities necessary to perform the text mining; the third stage concerns the assessment of the homogeneity of the results, and the fourth stage analyzes the information in each group.

3.1. First stage: building the dataset.

3.1.1. Company description.

Founded in 2008 through capital from social investment, CSMZ1 is an SB that has experienced rapid growth in Colombia’s northern region. Its purpose is focusing on the continuous promotion of rural families’ development in its area of influence. At the end of 2016, it had 53 offices, almost 165,000 families as its customers, 909 employees, and 81.3% of its assets in the hands of foreign investment funds. Its operating revenues amounted to almost USD 28 million, representing a growth of 20% compared to the same figure in 2015. Its vision for 2022 is to become an innovative rural bank providing service excellence throughout Colombia.

3.1.2. Data collection and sample composition.

We constructed a database from the transcripts of structured interviews conducted in February 2017 at the CSMZ headquarters located in the city of Bucaramanga, Colombia. In the first instance, and based on their apparent level of commitment, the company’s human resources department suggested ten possible respondents. Afterwards we interview four people chosen randomly out of those initially proposed. The following interviews were collected through the snowball sampling method (i.e., through the signaling, by participants, of individuals that were also considered highly identified with the company). In this way, when referrals pointed to the same individuals previously interviewed, the authors considered the study to have reached theoretical saturation (Corbin & Strauss, 2015; Mason, 2010). Consequently, we obtained a biased sample consisting of 34 highly committed and identified CSMZ employees. It is worth mentioning, and regarding sampling techniques in the search for theoretical saturation among qualitative studies, that this sample size amply satisfies the 12 interviews proposed by Guest, Bunce and Johnson (2006), and even duplicates the 17 interviews proposed by Francis et al. (2010).

The interviews were conducted in a face-to-face fashion, and each lasted between 21 and 28 minutes. The interview guideline contained 18 questions on four subject areas: Employee’s OID, the notion of CSR, perceptions about Normative CSR, and perceptions about Instrumental CSR. Initial questions were associated with OID concepts (Mael & Ashforth, 1992) in order to make sure the respondents had a high identification with the company. Thus, we only used the concept of OID as a means to approach respondents who enjoyed belonging to an SB to enable them to talk freely about the CSR actions performed by this organization. Following questions were meant to elucidate how respondents understood and felt about the concept of CSR in light of what CSMZ defines and performs as CSR actions. These questions include inquiries about their feelings concerning the company’s identity and the accomplishment of social and financial goals. Furthermore, some other questions concentrated on perceptions in terms of the CSR adopted at organizational level, taking a deontological perspective (i.e., how connected they perceived CSMZ’s intentions with actions in terms of its performed CSR). Final questions were oriented to establish a comparison between the employee’s perceptions and the normative and instrumental notions of CSR (Amaeshi & Adi, 2007; Swanson, 1995).

At a later stage, and in order to prepare the corresponding analysis, we transcribed verbatim the 34 interviews, generating 34 different documents in flat texts format without the guiding questions asked by the interviewer in order to generate a database consisting only for definite answers. As a side note, we carried out the data collection in Spanish and adapted the results to English for the present manuscript.

3.2. Second stage: text-clustering analysis.

In general, text clustering is an AI technique that seeks to group documents (in this case, interview transcription) into sets that have a related implicit structure (Yu et al., 2011). Two simultaneous objectives characterize the distribution of these groups: a) To maximize the similarity between the elements of the same group (i.e., grouping the answers with the most related language structure); and b) To maximize the differences between groups (i.e., dividing the population into some subsets such that there is a substantial disparate language structure between clusters) (Mugunthadevi & Punitha, 2011). For this purpose, it is necessary to generate an initial data preprocessing, which was performed using the statistical software R with the “TM” (Feinerer, Hornik, & Meyer, 2008) and “SnowBallC” (Bouchet-Valat, 2014) packages. The process consisted of removing those natural language characters such as exclamations, interrogative marks, scores, and other elements that connote language but are not words. Subsequently, we also eliminated “stop-words” from the documents (i.e., articles, pronouns, and prepositions, among others). The above-preprocessing actions are justified as these elements are usually present at a high frequency in natural language but lack a concrete meaning, and thus impart “noise” in the results.

Later, and in order to synthesize the meaning of the natural language, it is required to transform all words into their linguistic root. Subsequently, documents are converted from flat texts into a numerical format by creating a matrix that crossed the words frequency (columns) with the corresponding original document (rows). This transformation allows to identify which words are the most frequently used by interviewees and to formulate a matrix of co-occurrence between terms (understood by the related appearance of terms in each document). Additionally, from the matrix of terms for documents, it is also possible to calculate the weight of each word identified (i.e., a relation between the high word frequency in each interview and the identification of unusual words across the whole interviews). As a way to illustrate better the above description, consider the following short example of four document (answers):

Document number 1 (D1): “CSMZ is very important for me, in CSMZ I am learning to see my life”; Document number 2 (D2): “CSMZ is my first job”; Document number 3 (D3): “I have many responsibilities in CSMZ; they are essential for me”; Document number 4 (D4): “I really like the purpose of CSMZ”. After the terms cleaning process, the word frequency matrix is presented in Table 2.

Table 2 Document-term frequency matrix.

| CSMZ | Important | Me | Learn | See | Life | First | Job | Have | Responsibility | Like | Purpose | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| D1 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| D2 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| D3 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| D4 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 |

Source: own elaboration.

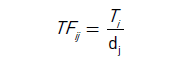

The weight of terms or words identified is formulated by the relationship between the frequency of occurrence of a term (TF) and the inverse frequency of the document containing the term (IDF). TF is the sum of all appearances of a term for each document (relative occurrence frequency), while the IDF factor of a term is inversely proportional to the number of documents in which that term appears, thus seeking to highlight non-generic terms (words less used in documents). Below there are the equations for factors calculation.

The frequency of the term Ti in the document dj.

This is the importance of the term where N is the total number of documents and df(t) is the number of documents containing the term t, as shown in Table 3.

Table 3 IDF Calculations.

| Word | df | N | IDF | Word | df | N | IDF |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CSMZ | 5 | 4 | 0.301 | First | 1 | 4 | 0.602 |

| Important | 2 | 4 | 0.125 | Job | 1 | 4 | 0.602 |

| Me | 2 | 4 | 0.301 | Have | 1 | 4 | 0.301 |

| Learn | 1 | 4 | 0.602 | Responsability | 1 | 4 | 0.602 |

| See | 1 | 4 | 0.602 | Like | 1 | 4 | 0.602 |

| Life | 1 | 4 | 0.602 | Purpose | 1 | 4 | 0.602 |

Source: own elaboration.

In this way, the weight of each word in a given document is the product of its frequency of appearance in the document (TF) with its inverse document frequency (IDF) - TF*IDF(tdt). From this relative weight, is generated the matrix for the word document in Table 4. Moreover, the grouping is performed by putting together those documents (interviews) close to each other, and taking into account a distance between the weight term vectors.

Table 4 TF-IDF calculations.

| Term | D1 | D2 | D3 | D4 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CSMZ | 0.301 | 0.602 | 0.602 | 0.602 |

| Important | 0.602 | 0.602 | ||

| Me | 0.602 | 0.602 | ||

| Learn | 0.602 | |||

| See | 0.602 | |||

| Life | 0.602 | |||

| First | 0.602 | |||

| Job | 0.602 | |||

| Have | 0.602 | |||

| Responsibility | 0.602 | |||

| Like | 0.602 | |||

| Purpose | 0.602 |

Source: own elaboration.

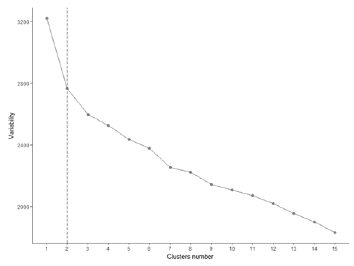

The current work uses a clustering technique known as bisecting k-means. This technique is characterized by forming clusters with hierarchical adjustment and, according to Karypis, Kumar and Steinbach (2000), combines the speed of calculation of k-means with the quality of the groupings of hierarchical clusters. For the development of such groupings by the application of the B-kmeans, it is necessary to begin from a single group that comprises all individuals (population group). Then, this population group is divided into two different subgroups (i.e., bisection) in such a way that the maximum similarity between their individuals is generated. Once these two subgroups are obtained, we select the cluster with the lowest degree of similarity; next, we divided it again creating two new subgroups. It is necessary to apply the bisection process to the new cluster with the lowest degree of similarity until getting the desired cluster quantity (taking into account the Elbow Method variability change).

Finally, we analyze the documents in each cluster in order to identify the similarity between interview answers. In Figure 2 there is the general text mining process description. In the present work, the R “cluster” (Maechler, Rousseeuw, Struyf, Hubert, & Hornik, 2017), “Factoextra” (Kassambara & Mundt, 2017), “dendextend” (Galili, 2015), and “fpc” (Hennig, 2015) packages were used for creating clusters. Also, “ggPlo2t” (Wilkinson, 2011) and “WordCloud” (Fellows, 2014) packages were used for the visual representation of the data.

3.3. Third stage: assessment of homogeneity (results reliability).

To identify the uniformity of the interview responses, it is required to determine the final quantity of clusters. In order to do that, we use a technique based on the clusters global variability called Elbow Method. The main idea is to run k-means clustering on the dataset for a range of values of k groups, and to calculate (in each value of k) the sum of squared errors (SSE). Once the SSE plot is created, it is needed to identify a discontinuity in slope and select the corresponding clusters number. In this work, we select the measurement of cosine similarity calculated as the point product among the normalized word vectors of each document. After making the comparisons, the average vector of similarity is calculated. The norm of this vector indicates the general similarity of each cluster (a high similarity implies high reliability in each cluster response).

3.4. Fourth stage: content analysis.

In each identified cluster, we achieve an inductive content analysis with emergent coding as a hermeneutical phase. This is done by establishing the categories in five steps initially applied by Elo and Kyngäs (2008): open coding, development of coding sheets, grouping, categorization, and abstraction. Therefore, this content analysis takes into account the CSR normative-instrumental tension and its characteristics as a coding framework. Finally, we analyze the characteristics of the interviewees with the purpose of determining if there are detailed profiles among the members of each group, taking into account variables such as gender, position in the company, salary, and age.

4. Results.

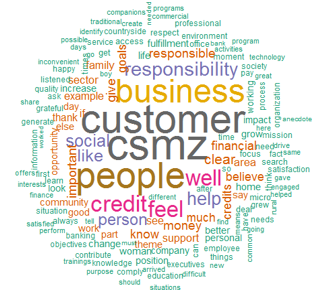

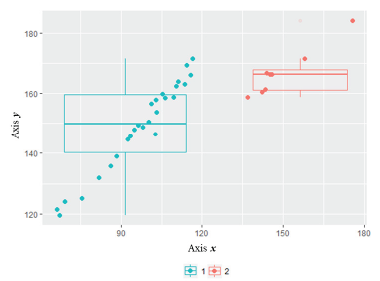

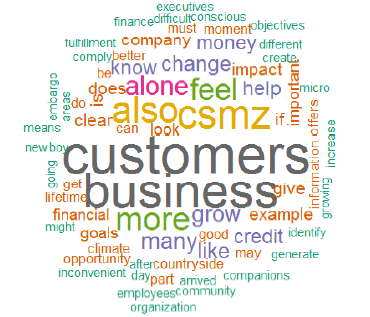

Once we get the numerical weight matrix, it is possible to analyze the relationships between terms. In Figure 3, there is a graphical approximation that shows a relation between the company’s name and both its employees and customers, followed by elements of its portfolio services, and by some terms related to its CSR practices, indicating a possible latent relationship. To determine whether subgroups existed within the interviews, we applied the Elbow Method to the matrix of TF*IDF(td). Two large groups of respondents were subsequently founded (Figure 4). After this, we conducted a comparison between different link methods and their respective distances, finding that the best combination is the Hartigan Algorithm with Manhattan distance.

4.1. Interview clustering.

Taking into account the Elbow method, we identify two clusters. They explain the variance distribution of the interviews by 60.14%. A first cluster formed by 26 people, who consistently referred to the company’s CSR internal practices oriented to improve the products and services offered to the customers, and the financial benefits that the company obtains from that. Conversely, a second cluster consisted of eight people who, by their way of answering, usually related the corporate image to the direct treatment of people, the company’s contribution to their quality of life and the CSMZ’s human resource development. Figure 5 shows the spatial distribution of the language structure used in the answers in each cluster, where the group number 1 (on the left side) corresponds to the instrumental CSR perception and the group 2 (on the right side) to the normative one.

4.2. First cluster description.

A typical pattern in the first and most significant group of interviewees is the perception that adopting CSR is a beneficial factor for CSMZ. They believe that CSR actions carried out by the company derive from the fulfillment of their daily processes and goals and that, in turn, these actions are usually rewarded in terms of a better image, cost savings, and attraction of more clients, among other things. Many of them imply that such actions, which are valuable to society, should also be considered valuable to the company.

The 26 interviewees belonging to this first group consistently mentioned, among other CSR experiences, the participation in specialized events, the application of policies for the management of solid waste, and the social impact achieved through the credit facilities granted to the business projects of their clients. However, among the analyzed responses, the perception is that the company usually relates the effectiveness of its processes to the level of customer satisfaction and that, based on business growth, the generation of value is achieved for customers as well as for the company.

Additionally, it is perceived that, for most members of this group, the company makes constant advertising of its CSR policies as a practice that ratifies its social character. As an example, one of these employees highlighted the following comment: “During our meetings, usually, CSMZ members share their personal goals and objectives, and highlight how they fit with the company. Every day, staff are encouraged, and the company gives recognition to the achievement of goals and suggestions for those who do not do so well”. Figure 6 shows the words mostly used by the interviewees of this cluster.

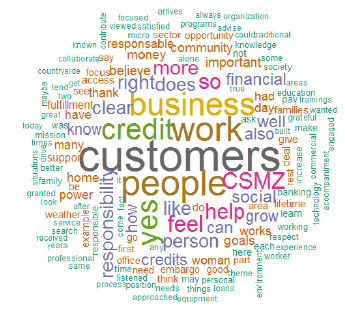

4.3. Second cluster description.

For the eight interviews grouped in the second cluster, CSR was defined as a disinterested reason for adopting practices that coincide with a more deontological dimension. That is to say that, in one way or another, they believe CSMZ must implement CSR activities without expecting anything in return, as a kind of work that every company ‘must do’.

In addition to emphasizing a sort of genuine spirit of responsibility for CSMZ’s actions, responses focused more on dealing with customers, their vulnerable condition (typical of the Colombian rural environment), and the positive impact of the company’s actions on the quality of life and well-being of other stakeholders. Incidentally, among other related characteristics of this group’s members, the specificity of their educational condition is a common element to highlight. Interviewees expressed satisfaction with their career at the company and, at the same time, about being able to participate in training focused on personal care and work. This translates into a more pleasant working environment in which personal knowledge, development, and satisfaction for actions are shared; moreover, those actions are related to the positives experiences in many financing projects developed by CSMZS’ employees. As an example of the above, one of the employees that is part of this group highlights the following comment: “I like working for the company, I like the purpose of CSMZ, and identify with it. At the moment, I am in the Public Relations Department, and feel that I am able to live more closely to the company and be more aware of the social impact that it has for people with scarce resources.” Figure 7 presents the most used words in interviews.

4.4. Group homogeneity.

Once the similarity among all members of each cluster is determined, we calculated the average vector norm. The findings show that the first group has a similarity coefficient of 0.7345 and, for the second one, a similarity of 0.803. Since values close to 1 indicate that there is homogeneity among the people surveyed and assigned to each group, we can assert that the study can be considered reliable. Lastly, after reviewing the different characteristics of each interviewee, we find that homogeneity is based on the employees’ responses and not on variables such as gender, position in the company, salary, and age. Therefore, there are not profiles in common between the two identified groups.

5. Conclusions.

The purpose of this paper was to identify how highly identified SB employees understand the notion of CSR concerning the conceptual tension between normative and instrumental perspectives (Aguilera et al., 2007; Amaeshi & Adi, 2007; Swanson, 1995). To do this, the present work deployed a qualitative study which was achieved by exploiting two main theoretical antecedents. On the one hand, by taking advantage of SBs’ nature as social value creators (Ogliastri et al., 2015), and therefore CSR performers par excellence. On the other hand, acknowledging the connection between CSR and OID (Jones & Rupp, 2017), thus using OID as a means to approach perceptions of CSR in an organizational context. Furthermore, this work attended some suggestions from Choi and Majumdar (2014), Littlewood and Holt (2018)) and Spence (2016), who highlighted the underdeveloped level of scholarship in the study of SBs in light of their CSR performance. In this sense, by inquiring as to the level of importance of intentions in performing CSR actions, and supported by AI tools, this work found a certain level of cohabitation for both notions of CSR in a micro financial institution in the Colombian context.

Results obtained from the analysis of the interviews conducted in CSMZ are consistent with previous theoretical postulates, which show that CSR and employee’s OID are conclusively linked between them (El Akremi et al., 2018; Farooq et al., 2016; Gils et al., 2017; Hameed et al., 2016; Jones, 2010; Kim et al., 2010; Korschun et al., 2014; Lamm et al., 2015; McShane & Cunningham, 2012). This link was evident since respondents (who were highly identified employees) unanimously manifested acceptance and trust in every organizational CSR action and decision. Likewise, in the responses analyzed, an effect can be seen of those elements on individuals’ perception of themselves as part of such a company. Expressions associated with company identification, feelings, as well as terms related to CSR have a dominant presence in the analysis performed - in all their notions - and demonstrate a high level of correspondence between them. Similarly, there is, in the consulted individuals, general confidence regarding the actions carried out by the company in line with its social purpose. That is, in a consistent fashion, the level of credibility regarding the authenticity of the company’s CSR actions seemed to be quite high.

Nevertheless, regarding the composition of the two groups finally obtained, it is worth noting that this particular finding is indeed dissimilar concerning several theoretical postulates. Since there was a significative difference between the number of individuals present in both groups, it is evident that the instrumental notion of CSR took precedence over its normative sense within the SB under examination. To start, it is palpable how the above idea leads this work to reject the hypothesis previously proposed. And while this could be perceived as, somehow, a challenge to what is proposed by Ogliastri et al. (2015) and especially by Cornelius et al. (2008) and Defourny and Nyssens (2012), the present work suggests that the findings mentioned above have the potential to enhance those postulates instead. After all, because of their specific nature, SBs are meant to deal, in a permanent fashion, with conflicting interests (Doherty et al., 2014). Thus, a deep understanding of their dynamics (which is the base of the present work) represents both a useful and indispensable endeavor for the current organizational scholarship.

In that order of ideas, the first contribution of the present work revolves around its findings. In doing so, it considers the different CSR conceptions present in the relevant literature (e.g. Aguinis & Glavas, 2013; Amaeshi & Adi, 2007; Brammer et al., 2007; Matten & Moon, 2008; Swanson, 1995; Tetrault- Sirsly, 2012), and came up with the conclusion that the analyzed data revealed a precise adaptation to the opposing concepts of normative and instrumental CSR (Amaeshi & Adi, 2007; Swanson, 1995) over other approaches. The results, thus, aimed to tackle the suggestion of Littlewood and Holt (2018) and Spence (2016), in the sense that more research is still needed for examining CSR as part of a purpose-driven company. They also indicate that, when considering the employees’ sense of identification and the company’s socially responsible approach, two very different types of employees can coexist in an SB such as the one examined, even in a noticeably unbalanced fashion - a minority that is confined to the normative concept of CSR, and a majority that has a more instrumental orientation.

In the first group, employees were found who privilege the pursuit of financial rewards through the implementation of CSR. Their sense of belonging to the company is linked to the notion that CSR contributes to profit maximization (Friedman, 1970) or to building the company’s competitive advantage (Porter & Kramer, 2011). These people often relate socially responsible behaviors with several organizational initiatives, such as fair disclosure of purposes and policies (rhetoric), the search for social/environmental certifications, and the granting of donations seeking tax benefits. To a certain extent, they even find meaning in the adoption of practices, identifying them as motivating the organizational human talent and, therefore, as a redundant way of obtaining benefits through the improvement of the individuals’ performance (Jones & Rupp, 2017).

For the second group, employees feel identified with the company because it privileges “intentions” over “rewards” in adopting CSR practices. They see the company as truly a SB that acts according to what must be done, beyond whatever generates an advantage, a profit, or a saving. This type of conception is centered on the moral sense of the CSR concept (Swanson, 1995), and it suggests that employees are attracted to the company because the company is doing “the right thing”. It is proposed that, under this conceptual framework, employees act voluntarily and actively in order to obtain more socially fair and sustainable results for society (Higgins, 2010).

The reasons for this behavior could be framed in terms of the different institutional pressures coming from the environment, or in terms of the characteristics of the individuals studied (Delmas & Toffel, 2004). However, beyond deepening in those possibilities, the present work aimed to understand a social phenomenon rather than determine its causes. In this vein, two mutually exclusive scenarios able to explain the findings plausibly were acknowledged. One first scenario, does not take into consideration the respondents’ dissimilarity between notions of CSR, but prefers to be focused exclusively on their coexistence. This could be a situation of clear complementarity of ideas in which both CSR views emphasizing each other’s qualities in a contemporary way. In turn, a possible second scenario does take into consideration the clear domination of instrumental CSR over normative CSR when analyzing our results (visible in a ratio of 3:1). Here, the evidence could suggest a potential distortion of the moral concept of CSR in light of the individuals’ sense of belonging, which occurs even in purpose-driven backgrounds.

Since it could be interpreted as a constructive phenomenon, the former case seems not to represent a problem for the sake of achieving common organizational goals of development (Schreck, Van Aaken, & Donaldson, 2013). After all, any company could be the perfect example of how both conceptions can reconcile each other. However, for the latter case, the reality also could be that given that under the dominance of the instrumentalist CSR conception (Marais, 2012), several concerns related to the company’s core purpose could arise and be problematic in terms of its decision-making process.

In this way, the case of CSMZ could represent a situation that demands attention, wherein the pure deontological perspective of the CSR concept can be compromised and its socially-oriented purpose distorted. Nevertheless, in this work (and probably moved by their desired) authors suggest that instead of a probable defeat of the moral concept of the CSR, the prevalence of the instrumental notion over the normative one has the potential to represent a situation in which both views complement each other by emphasizing each other’s virtues and qualities. In any case, more scholarship would be necessary in order to figure out a better level of precision in this matter, as well as further implications for this finding.

Although theoretical in form, the second contribution emerges from a more practical point of view. It implies that both facets of the CSR can be positively correlated with desirable individual attitudes and behaviors in SBs. The latter implies that regardless of the conception that an employee can possess about the CSR concept (i.e., either normative or instrumental), the CSR itself can act as a positive source of looked-for outcomes in companies, like employee engagement, job satisfaction, and corporate citizenship, among others. The reason for this lies in the fact that previous research in the field of organizational behavior locates OID, if not as the quintessential antecedent (Farooq et al., 2016; Korschun et al., 2014; Lamm et al., 2015), at least as an essential mediator on the relationships between CSR and such attitudes (Aguinis & Glavas, 2012; Jones & Rupp, 2017; e.g. El Akremi et al., 2018; Gils et al., 2017; Hameed et al., 2016). In that sense, just as the same thing apparently can happen with any given employee who defends a normative orientation of the CSR, employees considering that CSR should respond to an instrumental focus, are also able to reflect an improvement on their OID, which subsequently will be reflected on other behaviors and attitudes.

Finally, the third contribution of this work is represented by its methodological nature. On the one hand, the lack of qualitative approaches to tackle the questioning at issue was evident in the literature review previously presented (McShane & Cunningham, 2012). On the other hand, to the best of the authors’ knowledge, there has not been, to date, any attempt to use AI devices in order to analyze data related to the link between CSR and OID in any company (and particularly in SBs). So far, no work has been developed aimed at comparing the normative/instrumental façade of the CSR in conjunction with various organizational outcomes either. Therefore, the way for using a novel approach in these kinds of studies was practically paved. In that sense, the present work took advantage of this reality, which at the same time has the potential to open several future works for a more refined development in the field.

The present work is subject to some limitations. Firstly, it can be claimed that the sample size does not represent a significant portion of the population (34/909), which could lead to several issues in generalization. Nonetheless, it is necessary to emphasize that, considering the qualitative nature of the study design; its conformation was focused on a single singularity present on the recruited individuals, namely their OID according to either the company’s management perception or those who were previously recruited. Furthermore, the use of the snowball sampling technique complemented with the achievement of theoretical saturation (Corbin & Strauss, 2015; Francis et al., 2010; Guest et al., 2006; Mason, 2010) also helped to deal, in part, with such shortcomings.

Moreover, an essential argument for facing the previous matter comes from the theoretical pretensions of these kinds of works. Together with case studies, empirical exercises have also helped illustrate the theoretical approaches that were discussed, and contribute to the deductive generation of new knowledge. However, the objective of its use is not yet to immediately generalize the results to the population, but rather to promote a potential theoretical transferability of their contributions (Tsang, 2014). This is achieved through rigorous research application, improving the quality of data collection, and raising the internal validity and construct validity of the constructs used (Gibbert, Ruigrok, & Wicki, 2008). While for the first two conditions (rigorousness and data quality) this work explicitly states having proceeded with acuity and competence in a given work plan, for the last two (internal validity and construct validity), it was clear that this work also represents an in-depth study of the context and the application of a specific research protocol that involved continuous approaches to data and theory.

As another concern, the context studied seems propitious since countries like Colombia, and most of the Latin American countries are characterized by deep social needs where the productive sector could be a determining factor in the achievement of their developing goals (Aquino- Alves, Reficco, & Arroyo, 2014). Additionally, studying this phenomenon in a company that, as in the case of CMZS, has a direct orientation towards social responsibility, allows for a better understanding of the conditions governing the mentioned “CSR dual face”.

Future research efforts could be directed toward mitigating the limitations mentioned above. Mainly for the sake of improving external validity, similar studies can be undertaken in other types of organizations or other environments, with new and more refined statements. Just as an example, as far as it was researched, there is still no real application of a mixed research design in which different skills in the field of organizational behavior are evaluated under the consideration of the social and environmental performance of social enterprises. The door is, therefore, open to further research on the corresponding topics and their enriching among different contexts.