ARTICLES

A snapshot of training practices in Peru

Visión general de las prácticas de capacitación en Perú

Visão geral das práticas de treinamento no Perú

OLIVIA HERNÁNDEZ POZAS, Ph.D.*; KETY LOURDES JAUREGUI, Ph.D.**

* Director of the Master in International Business and full-time professor in Management at EGADE Business School, Instituto Tecnológico y de Estudios Superiores de Monterrey, México olivia_hdz_p@itesm.mx.

** Director of the Master in Organization and Management of People and Associate Professor in the Management field at the Graduate School of Business, ESAN University, Peru. kjauregui@esan.edu.pe.

Autor para correspondencia. Dirigir correspondencia a: Alonso de Molina 1652, Santiago de Surco, Lima 33, Lima, Perú.

Recibido: 3-jun-11, corregido: 31-mar-12 y aceptado: 10-ago-12

Clasificación JEL: M5, M530

ABSTRACT

Organizations need well trained employees in order to maintain a competitive advantage. The purpose of this paper is to describe current training practices in Peru and to provide recommendations for improving organizational performance. This paper also aims to set priorities for future research work. Human capital theory and contributions on need assessment, and training planning, implementation and evaluation served as theoretical framework. This is a cross-sectional, exploratory study that used information from surveys conducted in 24 Peruvian companies. The findings reveal a strong interest in training, particularly with regard to the improvement of competencies, preference for face-to-face training, and the use of reaction evaluation methods. The recommendations include, among others, improving the provisions for internal support, policies, technology, behavioral evaluation, and resources.

Keywords. Training; need assessment; human resource management.

RESUMEN

Las organizaciones necesitan empleados bien entrenados para mantener una ventaja competitiva. El propósito de este artículo es describir las prácticas de capacitación en organizaciones en Perú, para entregar recomendaciones que mejoren el desempeño organizacional. Este artículo también ayuda a establecer prioridades de investigación futura. La Teoría de Capital Humano y contribuciones de evaluación de necesidades, planeación, implantación y evaluación de la capacitación sirvieron como marco teórico. Es un estudio exploratorio de corte trasversal, usando encuestas en 24 compañías peruanas. Los resultados revelan un interés fuerte en capacitación, particularmente en competencias, preferencia por capacitación cara a cara, y uso de métodos de evaluación de reacción. Las recomendaciones incluyen mejor provisión de apoyo interno, políticas, tecnología, evaluación de conductas y recursos.

Palabras clave. Capacitación; evaluación de necesidades; administración de recursos humanos.

RESUMO

As organizações precisam de funcionários bem treinados para manterem uma vantagem competitiva. O propósito deste artigo é descrever as práticas de treinamento em organizações do Perú, para gerar recomendações que melhorem o desempenho organizacional. Este artigo também ajuda a estabelecer prioridades para futuras investigações. A Teoria de Capital Humano e contribuições de avaliação de necessidades, planeamento, implantação e avaliação do treinamento serviram como marco teórico. É um estudo exploratório de corte transversal, usando pesquisas em 24 empresas peruanas. Os resultados revelam um forte interesse no treinamento, em particular nas competências, preferência por treinamento pessoal e o uso de métodos de avaliação de reação. As recomendações incluem melhorar a prestação de apoio interno, políticas, tecnologia, avaliação de condutas e recursos.

Palavras-chave. Treinamento; avaliação de necessidades; administração de recursos humanos.

Introduction

The success and survival of any organization depends on how well it can maintain and gain market share in a particular industry. In order to achieve this goal, organizations constantly need well prepared employees. Only those employees with the right and updated knowledge, skills and behaviors can make a real difference for the companies where they work. Thus, appropriate employee training becomes a critical component in any organization's strategy.

Forces such as, changes on demographics and the diversity of the work force, globalization, as well as an increased value placed on knowledge and new technology, are currently influencing the workplace and training (Noe, 2002). Upon these challenges, how ready are Peruvian companies? How much attention are these companies giving to training? What are current practices of training? And, how much of the current theory on training is being applied by these organizations?

Although training has proved to be important for organizational survival and growth, very little research has been found to answer these questions on training practices in Latin America. Therefore, more information is needed to better understand this phenomenon, as well as the causes and effects of its deviations from theory.

This paper attempts to contribute to the literature and the practice of training in Latin America examining current practices in the region. In this research, revision was done particularly in Peru. Thus, the purpose of the paper is to describe current practices of training in Peru and the delivery of recommendations that can improve organizational performance. This paper also aims to set priorities for future research.

The structure of this paper is as follows: First, the theoretical framework is presented. Second the methodology is explained. Third, results are exhibited and discussed. Finally, conclusions and recommendations are developed.

1 Theoretical framework

Training and development refer to a set of activities, planned by a company, to improve employees' capacities, skills and behaviors. Gilley, Eggland & Maycunich (2002) define training as ''identifying, assessing and arranging planned learning efforts that help in the development of the essential competencies that enable individuals to perform current jobs'' (p.9). While training focuses on a current job, development looks for the future job (Harris & DeSimmone, 1994). The purpose of training is for employees to master certain knowledge, skills and behaviors and apply them to their day-to-day activities (Noe, 2002). The purpose of development is for employees to get prepared, with knowledge, skills and behaviors, to new challenges and opportunities in their workplace.

Theoretical foundations of Human Resource Development include Economics, Psychology and Systems Theory (Lynham, Chermack and Noggle, 2004). In the 1950's, attention to human capital increased when development theories shifted away from physical capital and infrastructure (Blunch & Castro, 2007). According to Human Capital Theory (HCT) created by Schultz (1960) and popularized by Becker (1962, 1964, 1993) organizations should consider employee expenditures, such as education and training, as an investment. Lately, it has been theorized that the ability to learn faster than your competition may provide competitive advantage (De Geus, 1997).

Nowadays, organizations use training and development to increase value to their human capital and to gain competitive advantage. The state of the industry report, published in 2011 by the American Society of Training and Development, showed that organizations are committed to the delivery of knowledge and the development of their employees. This means, companies believe the appropriate and effective use of training & development becomes crucial for their business growth and success.

According to Truelove (1995) every organization has training policies, however, not all are in a written form, and some of those organizations which have them in a written form, do not widely publish them. The value of having a set-down policy statement helps to maintain a consistency throughout the organization (Truelove, 1995). Typically, a training policy includes the aims and objectives of the training function, responsibilities for identifying training needs, training budgets and the training plans, among several descriptions of types of training the organization is considering.

Once a training policy has been established, the training design process starts. A training design process typically includes four steps (Noe, 2002). Step 1 is to conduct needs assessment. Step 2 involves the design of the step 3 implementation plan. Finally, step 4 refers to the evaluation and improvement of the training plan.

1.1 Needs assessment

Needs assessment usually is the first step in the training design process. According to Noe (2002), typical outcomes of needs assessment include (1) what trainees need to learn, (2) who receives the training, (3) type of training, (4) frequency of training, (5) buy versus build training decision, and (6) training versus other human resource options such as selection or job redesign. If needs assessment is poorly conducted or not conducted at all, the company will not receive training benefits.

It also usually consists of McGhee & Thayer's (1961) three-level analysis: organizational, task and person analysis. Organizational analysis links strategic planning with training. According to Goldstein (1986), it is in organizational analysis where organizational goals and strategy are identified, as well as, where the allocation of resources and the environmental constraints are determined. The next level of analysis –task analysis– identifies the content of training is needed for a particular task or job. Basically, task analysis includes (1) development of an overall job description, (2) identification of the task, (3) description of Knowledge, Skills and Attitudes (KSA), needed to perform the task, (4) identification of those areas that can benefit from training and (5) establishment of priorities among areas (DeSimmone & Harris, 1998). Finally, person analysis identifies who should be trained and what kind of training they need (Anderson, 2000). According to McGhee & Thayer (1961), person analysis is divided in two: summary person analysis and diagnostic person analysis. While the first one determines the overall success of an employee's performance, the last one searches the main reasons for such a performance. Person analysis may be difficult and costly (Herbert & Doverspike, 1990).

A variation of needs assessment is Gilbert's Exemplary Performance Improvement Chart (EPIC). In this approach, desired performance outcomes are defined first; then, barriers are identified. In this approach performers do most of the analysis (Anderson, 2000).

Needs assessment can be conducted using competency-based approaches too. A set of knowledge, skills, and attitudes, called competencies (McLagan, 1997), are specified for each specific position in a particular company. Each competency has a set of behaviors classified by levels of development (e. g. level one to five). Then, employees are evaluated (e. g. by observation of behaviors and impact on performance) and located in a specific level of development for each competency. The difference between their current level of development for a competency and the one needed for their position is the gap where the employee should receive immediate training.

Several techniques are used to conduct needs assessment, including observation of employees, questionnaires, reading of information on technical manuals and records, as well as, interviews with subject matter experts. Since no one technique is better than the others, multiple techniques are usually used (Noe, 2002). Main differences among techniques include the time they consume, the expert knowledge or skill they need, the precision of recorded data, and cost.

1.2 Plan of training

Once the need for training has been established, it is time to outline the training plan. Training plans are normally organized asking questions such as what kind of content is going to be included in training? Who is going to be trained? How are they going to be trained? When are they going to be trained? Who is going to train them? Where is training going to happen? At this point, when the training plan is been outlined, it is important to determine the boundaries of training. According to Truelove (1995), typical constraints which bound a design include (1) the training proposal: must job performance be achieved or can standards be relaxed?; (2) organizational support for training; (3) constrains related to those to be trained: their entry behavior, the numbers, availability for training, how many trainees at a time, for how long they can be released; (4) available resources: trainers, accommodations, aids, technical support, equipment; (5) training budget: preparation and running the training; (6) time to develop the design and materials; (7) duration of the event; and, (8) assessment: will individual assessment be required? What methods are acceptable? Who will access the results?

Variables which need to be considered when designing a training plan include content, sequence, place, trainers, time, methods and media. Truelove (1995) explains that decisions about these variables will be made within the previously described constrains.

According to Noe (2002) for learning to occur in training programs several conditions are required. Main conditions include meaningful material and content, clear objectives, skilled trainers, appropriate learning environment and opportunities for practice and feedback. For those to be trained, particularly for adults, it is important to know why they should learn. Employees may learn through many different methods, for example, through observation, imitation, hands-on workshops, practical experience or interacting with others.

Employees can also learn through the use of technology. In fact, technology has made it possible to reduce costs associated with delivering training and has allowed distance and non-real-time collaboration to occur (Noe, 2002). According to Jimenez, Sanchez and Sanchez (2010) most training programs are developed in the form of courses, allowing insight into the contents, but they also indicate that conduct training programs face to face limits assistance to employees, making it necessary to design training programs that include blended learning and new training technologies, which can reach the target with greater certainty. Examples of new training technologies can be multimedia, e-learning (e. g. web-based training, virtual classrooms, distance learning), expert systems, as well as, software applications among many others. Although, technology-based training has many advantages, it is important to consider that certain conditions should be in place, for example, sufficient budget, technological support and equipment, as well as, comfortable trainees using technology.

Competent training professionals are vital for training success. The American Society for Training and Development (ASTD, 2011) has identified five key training roles: analysis/assessment roles, development role, strategic role, instructor/facilitator roles, and administrator role (Rothwell, 1996 quoted by Noe, 2002). Depending on what the specific role of the training professional is, a set of competencies will be needed. Competencies such as understanding of adult learning, capacity to provide feedback, coaching, computer literacy, and project management are needed; but also, new competencies at a more strategic level such as understanding of industry and business.

1.3 Implementation of the training plan

The primary activity at this stage is the execution of the different integrated actions in the training plan. For that purpose, the person in charge of the plan must use different resources related to the engineering and quality management of the training.

1.4 Evaluation of the training

The evaluation of training is the foundation for its continual improvement and it is needed for determining the effectiveness of the training plan. Every year, companies invest millions of dollars in training programs looking for a competitive advantage, then, it is important to justify such an investment. Main reasons for the evaluation of training include: (1) to determine if the training objectives were the right ones in the first place, (2) to determine if these objectives were met, (3) to improve current and future training programs, (4) to improve trainers, and (5) to establish the cost effectiveness of the training plan (Truelove, 1995).

According to Van Wart, Cayer & Cook (1993) training evaluation can be formative or summative. While formative evaluation is the evaluation conducted to improve the training process, summative evaluation is the evaluation conducted to determine the extent to which trainees have changed as a result of the intervention. Formative evaluation involves the collection of opinions and beliefs about the training program. Summative evaluation involves the collection of evidence of learning outcomes, such as, acquired knowledge, skills and attitudes, as well as, changed behaviors. Summative evaluation may even measure monetary benefits (Noe, 2002).

The most widely adopted model of evaluation of training in business and industry is Kirkpatrick's (Anderson, 2000). Kirkpatrick's evaluation model is based on several articles written in 1959 for Training and Development Journal and consists of four levels: reaction, learning, behavior and results. According to Kirkpatrick (1996) the level of reaction evaluates how participants feel, it is a measure of customer satisfaction on the topic, the trainer, the program, etc. Typical methods to collect data for the reaction level include questionnaires, observation and interviews. The level of learning refers to acquired knowledge, improved skills and changed attitudes. Methods of evaluation for the learning level include tests or demonstrations of performance and skills. The behavior level involves a change in onthe- job behavior. It is related to the transfer of learning. Most frequently used methods to collect data for this type of evaluation include observation, interviews and surveys. Finally, the results level of evaluation relates with company's indicators such as increase sales, higher productivity, larger profits, reduced costs, less employee turnover and improved quality, therefore, they are usually collected by accounting, financial and statistical techniques.

Once the evaluation of training is completed, the improvement suggestions about the training plan should be given, and the training process starts all over again.

2 Methodology

The present research is a cross-sectional and exploratory study. A cross-sectional study collects and studies data, of a population's subset, at a single point in time. According to Zikmund (2003) an exploratory research may be justified when the researchers have a limited amount of knowledge about a research issue. Thus, this type of methodology can be used as a preliminary step that helps ensure that a more conclusive future study will begin with adequate understanding. Exploratory research may help in the diagnosis of a problem and to set priorities for future research. Its objective is to methodically gather data in order to acquire a description that will lead to new knowledge (Moustakas, 1994). When reviewing research on training, authors of this paper identified plenty of studies about training for developed countries and regions, such as the United States and Europe, but a need for a field-based exploration in organizations of Latin America due to limited amount of knowledge about training practices in the region. This preliminary study starts exploring research in Peru and may continue in the future either with more exploratory studies in other countries in Latin America or with future research as a case-study or correlation type of design.

The implementation of human resources processes in Peru is booming, formal recruitment of staff in private companies has increased by 38% according to the International Business Report survey 2012. Also according to the labor survey, developed by the Pontificia Universidad Catolica del Peru (PUCP) at Lima, 30% of workers have social benefits. However in Peru, there are also some weaknesses in the management of human resources. According to a study of the consulting firm Mercer and the Peruvian Association of Human Resources (APERHU), in the last year, six out of ten companies in Peru have lost key human talent and eight out of ten companies have resorted it increasing salaries to attract and retain staff. Therefore, identification of training needs and the development of training programs become important for companies that try to enable workers to have skills and competencies to perform their work.

A non-probabilistic sample (i. e. convenience sample) was used for this research. Participants were 24 companies in Lima, Peru who accepted to collaborate with this research answering a 43-question survey. All participating companies are companies that either belong to the ''Great place to Work'' list or are interested in being a great place to work. Companies belong to varied industrial sectors such as food, aviation, beer, pharmaceutical, manufacturing, fishing, retail, financial services, telecommunications and transportation.

All respondents work in the training area or training department. Some are even usually responsible for training. 48% of them are women and 52% are men. 60% of respondents are between 25–35 years old, 27% of respondents are between 36–45 years old, 13% of respondents are between 46–55 years old.

The 43-question survey contains both open and close questions. Before its use, this instrument was initially tested for clarity and validated with three companies. When needed, adjustments to the survey were made.

Topics included in the survey and later analyzed are the following: organization of the training and development unit, needs assessment, training plan, implementation of plan and evaluation of training.

In this exploratory research, data analysis was done using descriptive statistics. Frequency and percentages were calculated in Excel for all questions. Tables and graphs were prepared to illustrate this snapshot results in a more comprehensive way. Results were organized by topic: organization of the training and development unit, needs assessment, design of the training plan and evaluation of training.

3 Results and discussion

3.1 Organization of the Training and Development Unit

When exploring about responsibilities and positions of training professionals, some inconsistencies between the responsibilities and the name of the position (e.g. chiefs, coordinators, managers, analysts) were found. These findings may be explained because employees usually perform varied duties depending on what is needed at a time, however, if the name of the position do not concur with the responsibility, the implications will be confusion and misunderstandings. Therefore, a better description of duties of the training positions will help to avoid this problem.

Most of the surveyed people agreed the training management should be integrated with the human resources strategy, and others said it should be integrated with the firm's general strategy. By doing so, respondents believe workers could be enabled to perform efficiently through knowledge and skills development, contributing this way to the fulfillment of the firm's goals and objectives. This statement, given by several Latin American executives when surveyed, is consistent with what current theory advises (Truelove, 1995; Noe, 2002).

Regarding the main duties of the training unit, 87% of the respondents said the training unit is mainly focused on the design and elaboration of the training plan, and on the instructional design of the training programs. Additionally, 80% of the respondents stated that the implementation of the plan and the evaluation of the training activities, which include the identification of indicators, are important tasks of the training unit. Thus, it seems there is not much emphasis on managing the training unit; in other words, planning, organizing, managing and controlling the training unit itself. This could be explained because some firms only have one professional in charge of the training unit and not a team.

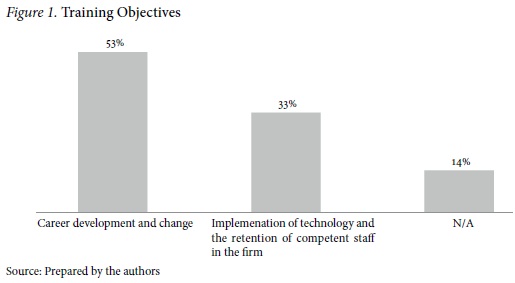

Respondents stated the training objectives are diverse: 53% consider training as a mean for career development and change, also for the improvement of the collaborator's attitudes towards work and the organization; and 33% of respondents mentioned training is related to the implementation of technology and the retention of competent staff in the firm (see Figure 1).

Regarding the focus of training programs, 87% of respondents sustained that training programs focus on the development of new skills, 80% stated that they focus on the acquisition of new knowledge, and 67% affirmed that they are oriented towards improving deficiencies, skills and/or knowledge.

Findings showed 33% of the topics covered in training programs, developed by the firm or outsourced from other companies, aim at the development of technical competencies; 22% refer to leadership issues; 19% are related to safety and environmental topics; 15% are related to other soft competencies (e.g. teamwork); finally, 11% focus on quality issues. These findings show firms are interested in having collaborators that, not only demonstrate technical competencies, linked to their careers; but also, demonstrate general competencies (e.g. leadership and teamwork), which allow them to have a personal and professional development. These findings may support new theoretical developments that criticized those training theories which in the past did not consider competencies that prepare people for their life, but only for their jobs (see Figure 2).

In addition, 53% of surveyed firms develop or outsource less than 10 courses/year; 20% of the firms from 11 to 30 courses/year; and 13% of the firms from 31 to 60 courses/year. Only 7% of the firms develop or outsource more than that, 60 courses/year. Few of these reported that they develop even hundreds or thousands of courses. Finally, 7% of the surveyed firms did not provide any data. It was observed that some of them did not have a record of their offered training. This heterogeneity in the number of courses delivered per firm could be explained by the variety in the number of employees in the organizations. It was noticed that the higher the number of employees, the higher the number of offered courses. Also, this data could be associated with the firm's core business, annual turnovers and promotions, within the organization, in order to develop a career line, which demands more preparation and education.

In 45% of the surveyed firms, training occurs when employees just start working in their positions, through induction programs or programs that are mandatory to achieve certain standards and quality norms. In another 45% of the firms, training is offered during an employee's work life at the firm. Only 10% of the firms aim to the development the worker's employability, when this is leaving the company. Thus, it is seen that these firms center their attention on training, at the beginning or during the employee's work life, rather than on outplacement.

Regarding the delivery of training using technology, 87% of the firms make use of only face-to-face training. The remaining 13% make use of blended modes. Among the surveyed firms, the use of e-learning, as the sole training mode, was not reported. This could be explained by the respondent's belief that only face-to-face training enables direct contact and interaction between collaborators and trainers, facilitating feedback processes.

As for the number of people working in the training area, it was found that only 11% of employees, who belong to the human resources area, were exclusively involved in training management. The other 89% of people were involved in the rest of the human resources processes. These percentages indicate the workforce appointed to work in the training area is rather limited in relation to the one allocated for the other processes of the human resources area. This explains why these activities are usually outsourced from external sources such as, consulting firms.

Likewise, an equally reduced percentage of employees, in the human resource area, were observed in comparison to the firm's total staff. human resources represent only 1.68% of total personnel, while training personnel accounts for 0.21% of it, in contrast to 98.11% of the staff working in other areas of the organization. These reduced percentages could be explained by the following reasons: an increased use of software in the human resources processes and by the decentralization of human resources processes. Decentralization usually involves the support of, either managers from other functional areas, or consulting companies.

All participating firms use some kind of software to develop the training processes in their organizations. From this group, 60% use specialized software, such as Systems Applications & Products in Data Processing (SAP) or any other customized program for the systematic management of each of their processes; 40% use the Excel program for support. These results show the firms' growing interest in improving the systematization of their training processes.

Regarding the training sites, 73% of the respondents pointed out that their training takes place, both in and out of the working site. This depends on the kind of training: business-related training is generally carried out inside the company, and training related to other topics, such as general competencies, are usually developed outside the working place. 13% of firms organize training exclusively ''out of the working place'' in order to minimize distraction. Some companies rent training sites, or reserve hotels or clubs among other training locations. Likewise, 13% of the companies hold training programs only ''in the working place'', as most of them have special areas where their collaborators are trained; though, their availability is limited due to the firm's operative work.

Regarding training schedules, findings revealed that 60% of these activities are held both during and after work, while 40% are held exclusively during working hours. There were no firms in the sample that organize training after working hours only.

In regards to training budget, it was found that 47% of firms invest less than 2% of their sales, 13% invest from 2.2% to 4%; and 40% did not provide this information. Some of the respondents pointed out that their budget is not fixed, so higher percentages could be used in case the organization needs to invest in additional training (see Figure 3).

3.2 Needs Assessment

Most of the surveyed firms sustained that training needs are influenced by the firm's strategies and objectives. Hence, respondents assured that priority is given to those training programs which contribute to the achievement of goals and objectives, aligned with the organization's strategy.

Results indicate that 40% of the firms identify training needs using a 360-degree performance evaluation; 20% by a gap analysis between the current and the expected competency-based profile of each position; other 33%, using individual interviews with collaborators and their bosses or supervisors, as well as, through group interviews with collaborators, regarding the alignment of competencies, objectives and priorities. Finally, only 7% remarked that needs is not a planned process (See Table 1). It originates when collaborators point out a training necessity along the time. These figures demonstrate that, nowadays, performance evaluation is a popular tool, frequently used by companies to diagnose educational needs and it is no longer associated only for remuneration purposes. Moreover, results show that in most of the cases, current practices of needs assessments do not reflect McGhee & Thayer's (1961) theoretical framework for needs assessment (i.e. the three-level analysis: organizational, task and person). If companies do not perform the analysis at its three levels, inconsistencies between organization, task and the person may appear.

Regarding competence-based training, 73% of the participating firms have a competence profile for positions. However, 27% of them have it only for some of the positions. Main reasons for this include: (1) newlycreated positions, and (2) firms that only have profiles for the operative positions. In addition, findings show that among these firms, that use tools for the identification of competencies, the most used tools are interviews (33%), competence tests (20%), and knowledge and psychological tests (13%). Other 34% of the firms usually determine their competencies in some other way, for example, by headquarters definition, or by regulations stated by the top management or the board. In sum, this indicates a varied combination of tools, used for the identification of competencies, being the interview as the most popular tool, though not exclusive.

When asked to grade their current processes of needs assessment, 40% of the firms considered the way they identify the training needs in their organization as good; 33% stated that it is very good; 20% said it is satisfactory; and only 7% qualified it as excellent. Figures show most companies qualified them as good. Nevertheless, most respondents expressed that they believed there were some issues that needed improvement. They added that every year they review their needs assessment means.

Hence, it seems that organizations are in the process of implementing changes that will substantially improve this process.

3.3 Design of the Training Plan

Most of the participating firms in this research (87.5%) have an annual training plan. This plan is generally reviewed every six months in order to do adjustments or improvements according to the reality of the moment and the market. However, 12.5% of the firms stated that they do not have a training plan, and training is developed depending on needs that come along the time.

Regarding people with the greatest influence in the different stages of the training plan, 80% of the respondents said that line managers and collaborators have the greatest influence upon needs definition; as for the design of training activities, human resources personnel, collaborators and line managers have the same influence. Nevertheless, regarding the implementation of the plan, human resources personnel assume the greatest responsibility, followed by division managers, and finally, by the collaborators. These results show that usually firms, in the initial processes of definition and design, work in teams, encouraging an open participation of the staff; while, the human resources area has a greater participation during the implementation stage. This happens in this way because human resources personnel are specialists in pedagogy and know better the administrative and logistics aspects of training as well.

Regarding the way the training plan is implemented, there are various responses and working schemes. 27% of firms take into account the evaluation of priorities and needs that emerge along the year and they execute their plan accordingly; 27% of the firms pointed out that the plan, previously elaborated determines the work to be done and the aspects to be dealt with; in other words, the plan guides them during the year. 13% of the firms consider that their plan's execution depends on the availability of time of their collaborators. This occurs in organizations with educational activities reduced to short periods, due to their work nature and the tight number of employees in operative positions. The other 13% of the firms mentioned that the execution of their plans is based upon the coordination with study centers or institutions, as well as, with consultants who become the trainers for certain specific issues. Finally, an important 20% of the respondents mentioned other ways to execute their plan. For example, some of them work jointly with area managers for the plan execution.

In response to the question of whether they received assistance for the design of the training plan or not, it was found that only 20% of the firms participating in the study, had some kind of support in designing their plans. 80% of the ones surveyed stated that the people in charge of training elaborated the training plan together with their team, line managers and other internal people. In this respect, one respondent commented that most of the people working in the training area had taken training management courses, so that they have knowledge (tools) to advise line managers in the development of the training plan of their area. This information shows that participating firms perceived as important, the fact that the training design, structuring and planning is developed by employees of the same organization. Main reasons for this include: (1) employees know and have direct experience in the business, and (2) they are clear on the organization's strategic objectives and the way work is conducted in it. Therefore, findings evidenced that external advisors or consultants are seldom used for the design of the training plan.

At this training stage, the different training actions are designed and programmed based upon the objectives of the training plan and the needs assessment. 80% of the training activities, offered by the firms to their collaborators, are workshops; 67% are seminars; 67% are courses; 27% are diploma courses; 27% are Master degree programs; 7% are coaching activities; and 7% are mentoring activities (see Figure 4). These results show that workshops are the most offered training activities for collaborators. Respondents sustained that dynamical activities allow for better knowledge acquisition and internalization of competencies and cultural values. This is known as learning by doing. Furthermore, the competencies, known as –generic competencies– such as, leadership, teamwork, creativity, and values are frequently demanded. In this regard, a respondent commented the following: ''We are not only interested in gaining knowledge, but values; thus, we use workshop''. It would be interesting for future research to review if values are actually changing by workshops –as executives think– or not.

Regarding the trainer's background, it was found that 86% of these organizations usually hire trainers that come from both, inside and outside the organization; only 7% of the firms have exclusively internal trainers, and only other 7% of the firms have exclusively external ones. The preference for internal trainers could be explained by the respondent's belief that internal trainers have better knowledge of the firm. However, external trainers are preferred for the development of general and technical competencies. Most of the human resource staff, in charge of training, remarked their interest in increasing the number of internal trainers. Again, the main justification is the belief that internal trainers know better the organization, and its needs.

In the case of internal trainers, 87% of the firms pointed out that their internal trainers are usually specialists from other areas of the organization, other 13% of the firms stated that their trainers belonged to the human resources department. In this regard, 80% of the firms stated that they develop their internal trainers, the other 20% of the firms said that they do not develop any internal trainer.

Now, in the case of external trainers, 73% of firms hire educational institutions to take care of the teaching and learning processes, 53% call consulting firms, and 40% request the participation of independent teachers. Additionally, 27% of the firms mentioned that they hire foreign teachers, and in some other cases, entrepreneurs or managers to share their experience. This data show that the great majority of firms hire services offered by universities, institutes and technical educational centers. However, a small number of firms seek to foster only good practices, so they look for entrepreneurs, managers and academicians.

3.4 Evaluation of Training

Training evaluation determines the extent to which the plan's objectives and the training activities are fulfilled. 40% of the firms evaluate their plans in terms of questionnaire based satisfaction assessment, 20% do so based on fulfillment indicators oriented towards the measurement of course and activity effectiveness. 20% use other criteria, such as, a comparison between the average training hours/participant to the number of trained employees in earlier periods. Additionally, other firms randomly choose and assess a small representative sample of the trained group. Some of the respondents remarked that they evaluate the training plans, by comparison to the initially-planned objectives. However, 20% of the firms reported that they do not evaluate their training plan at all due to time constraints. These data show the preference of organizations to evaluate training plans, solely upon satisfaction indicators. Nevertheless, some of them conduct their assessment based on achievement indicators, and only few focus on a global assessment of the whole annual training plan.

Most of the firms (73%) evaluate trainers through surveys and/or questionnaires which participants fill in, regarding content, methodology –including PowerPoint presentations, exercises and hands-on activities–, teacher-learner interaction, student's learning and given materials. Only 20% of firms use observation-based evaluations. Observation-based evaluations consist in having an internal trainer observing classes and assessing the achievement of course objectives. The rest, a 7% of the sample, stated that they do not conduct trainer evaluations at all, due to lack of time (see Figure 5). In most of the cases this happens because there are a large number of collaborators and/or training programs.

A large percentage of the firms (67%) do not evaluate the participants at the beginning of the training workshop or activity; only 33% of them administer these evaluations. Some of the respondents remarked that these evaluations are not necessary, as it is assumed that the staff attends the training courses without any prior knowledge.

Findings reveal that 93% of the firms do have a final evaluation at the end of the training process, but this only explores the degree of satisfaction of the training activity and the trainer. Still, 7% of firms do not perform any kind of evaluation of the trainer nor the training activity.

In spite of previous results, 54% of the firms reported follow-up and monitoring activities after the training, in order to know if there is a direct application of what has been learned in their positions. This is done by conducting interviews with supervisors and collaborators. Only 20% of respondents pointed out that participants are assessed through performance evaluation in their organizations, 13% are assessed through a non-structural observation-based monitoring in the field, and 13% do not carry out any of these evaluation procedures. These findings show that usually, the monitoring of goal achievement is based on surveys and on the direct supervision of bosses.

A strong interest of training staff on feedback processes was found. This contributes to the improvement of bosscollaborator communication. Some of the firms conduct follow-up procedures by putting the newly-learned issues into practice, for instance, by improvement projects. This is thought to be useful as it strengthens the entire training system and its influence upon the organization.

4 Conclusions & recommendations

Most sampled companies (93%) have a specific area dedicated only for training. This demonstrates the interest and commitment of these companies on improving its employees' knowledge, skills and behaviors. Probably, this is the reason that explains, all these companies belong or want to belong to the ''Great place to work'' list, which has positive implications. Nevertheless, inside the training department, the norm is not to find it divided by areas. The staff in charge of the training area is mainly involved in the design and implementation of the plan, giving little attention to Kirpatrick's behavioral level or results level evaluation of training. Based on these findings, the recommendation to companies is to dedicate more resources (e.g. time, money and people) to such types of evaluations, because according to current theory they add value to the organizations and allow these to better compete.

Results also showed that there are only few collaborators in the training area, as compared to other human resources areas. Although, this could be explained by a preference for decentralization of some of the human resources processes towards firm's functional areas; it was noticeable that also, consulting firms are been hired to develop some of these processes. Therefore, it is recommended not to forget to provide those companies with a strong internal support, the implication of not doing so, could be a waste of resources or a negative impact on company indicators. Additionally, since another explanation for a reduced training staff is the increased use of software for training processes, it is suggested a stronger technological support for training staff too.

The main training objectives, among surveyed firms, are either the developing of new knowledge and skills, or the improvement of deficiencies of current skills and knowledge. This can be seen with 73% of the firms having competency profiles (either defined by their main office, or developed by competency definition studies). The most demanded competencies are those known as –generic competencies– such as teamwork, leadership, pro-activeness, initiative, customer service and adaptability.

It was interesting to find out that, in addition to those benefits already expected from training, such as, improvement of KSA, a 33% of companies declared an improvement on organizational climate and motivation, as a result of training as well. From a practical point of view, this finding should help to justify next training investments, thus, companies must document it and report it to the management. Moreover, motivational theory may want to consider more deeply the exploration of training effects, and their relationships with motivation.

Regarding needs assessment, the most widely used approach is the competencybased model (60% of the companies). However, not all the companies have it fully implemented. Here, companies should continue working with the definition of competency-base profiles, because they are the foundation for the rest of modules, including training. The implications, for the training activities of continuing with incomplete competency-base profiles, could be inaccurate needs assessment in the first place, and inefficient training at the end. Additionally, a reduced percentage of companies use more than one needs assessment approach. Findings reveal that only 13% of the companies use the three-level analysis: organization, task and person. Considering that this is one of the most cited approaches of needs assessment in current training literature, it would be convenient to explore, in future research, why it has not been widely used in these Latin American companies. Also, figures show that 13% of the companies do not perform any kind of formal needs assessment before outlining the training plan. A study of causes and effects of this practice may also be considered for future research.

A lack of written training policies regarding the desired annual number of training hours for each position or group of positions was found. Since the value of having a set-down policy statement is that it helps to maintain consistency throughout the organization, then it is recommended to develop and communicate them every year. This way, every department and employee will know what is expected from him/her in this matter.

Findings related to the use of technology in training show that 87% of sampled companies have only a face-to-face type of training and just 13% has some kind of blending training (a mix of face-to-face learning and e-learning). Considering the technology opportunities, available today with e-learning, and their benefits, these figures represent an opportunity for change. Cultural reasons more than lack of opportunities or technological support explain these results. Implications of not adopting new technological alternatives of training may represent a competitive disadvantage for these Latin American companies.

A balanced mix between training inside and outside the workplace was found. Also, between training during working hours and out or working hours, and between the use of internal and external trainers. These results show a healthy combination of resources for training. Additionally, a preference for hands-on workshops, over seminars or other type of courses, demonstrates the practical approach of company training. Finally, the involvement of employees, managers and human resources staff, in varied training activities, such as, needs assessment, design, and implementation and evaluation of training, demonstrates collaboration within the companies in training matters. A positive implication of this collaboration includes the better application of training interventions, since those affected by training were part of the decision-making processes jointly with those who are experts on training.

Regarding evaluation of training, 40% of firms evaluate training at Kirkpatrick's reaction level, in other words, only based on customer satisfaction indicators. Another 20% evaluate with indicators of the fulfillment of training programs. Only 20% use results indicators. None declared learning or behavioral indicators, and 20% do not evaluate training at all. Clearly, most of the evaluation is formative. It pursues improvement of the training programs. This is not a bad idea, as a matter of fact it is needed, but it is insufficient. If companies keep evaluating training only in this way, the direct implication is that companies will have the training that people like, but not necessarily, the training that companies need. As it was mentioned before, a change towards the type of evaluation that Kirkpatrick has denominated as results level or behavior level will help in a better way companies to gain competitive advantage. Additionally, these types of evaluation are more consistent with a competency-based model that most companies are looking for. Therefore, it is recommended serious consideration to new training evaluation practices at Kirkpatrick's learning, results and behavior levels. Also, for future research, a study of better ways of using these three types of evaluation is recommended.

Findings and learning from this research can be compared, in future research, with other countries in Latin America to see if training practices, like those described in this study, are similar.

Companies in Latin America have young people who can be trained with the knowledge, skills and attitudes that are needed for competitive advantage. However, if training practices are not appropriate, such an effort would not be productive. Therefore, more collaborative research is needed to guide training practices.

Future research should focus on the collection of data in other Latin American countries to explore the generalization of the findings of this paper. Also, in the research of causes and effects, of differences found, in the State of the training industry in Latin America.

References

American Society for Training and Development (2011). State of the industry report. Available at: http://store.astd.org/Default.aspx?tabid=167ProductId=22697.

Anderson, J. (2000). Training needs assessment, evaluation, success, and organizational strategy and effectiveness. An exploration of the relationships. Disertación doctoral no publicada. Logan, UT: Utah State University.

Becker, G. (1962). Investment in human capital: A theoretical analysis. Journal of Political Economy, 70(5), 9–49.

Becker, G. (1964). Human capital. New York, USA: Columbia University Place.

Becker, G. (1993). Human capital: A theoretical and empirical analysis with special reference to education (3rd ed.). Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

Blunch, H. & Castro, P. (2007). Enterpriselevel training in developing countries: do international standards matter? International Journal of Training & Development, 11(4), 314–324.

De Geus, A. (1997). The living company. Boston, MA: Harvard University Press.

Desimmone, R. and Harris, D. (1998). Human Resource Development. Orlando: Dryden Press.

Gilley, J., Eggland, S. & Maycunich, A. (2002). Principles of human resource development (2nd ed). Cambridge, MA: Perseus.

Goldstein, I. (1986). Training in organizations: needs, assessment, development and evaluation. Monterey: Brooks/Cole.

Harris, D. and Desimmone, R. (1994). Human Resource Development. Fortworth: Dryden Press.

Herbert, G. and Doverspike, D. (1990). Performance appraisal in the training needs analysis process: a review and critique. Public Personnel Management, 19(3), 253–271.

Jimenez, S., Sanchez, R. y Sanchez, G. (2010). Los institutos de administración pública en España: programas de formación para el personal al servicio de la administración. Estudios Gerenciales, 26(116), 169–192.

Kirkpatrick, D. (1996). Revisiting Kirkpatrick's four-level model. Training and Development Journal, 50(1), 54–59.

Lynham, S., Chermack, T. & Noggle, M. (2004). Selecting organization development theory from an HRD perspective. Human Resource Development Review, 3(2), 151–173.

McLagan, P. (1997). Competencies: The next generation. Training and Development Journal, 51(5), 40–47.

McGhee, W. and Thayer, P. (1961). Training in Business and Industry. New York, NY: Wiley.

Moustakas, C. (1994). Research methods. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications.

Noe, R. (2002). Employee Training & Development. New York: McGraw Hill.

Schultz, T. (1960). Capital formation by education. Journal of Political Economy, 68(6), 571–583.

Truelove, S. (1995). The handbook of training and development. Oxford: Blackwell Publishers.

Van Wart, M.; Cayer, N. and Cook, S. (1993). Handbook of Training and Development for the Public Sector. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Zikmund, W. (2003). Business Research Methods. USA: Thomson.